My strongest memory of Brendon McCullum as captain is him flying through the air trying to stop some near-meaningless boundary. Not once, but again and again. Head first, soaring over the padded triangle, right towards the sponsor board with no sense of fear for his well-being.

But before that, McCullum did the same thing with his batting. It had this reckless energy to it. That at the time made little sense, but like the best-attacking batters, it made everyone bowling to him feel uneasy. You had to watch. He was spectacular in success and failure.

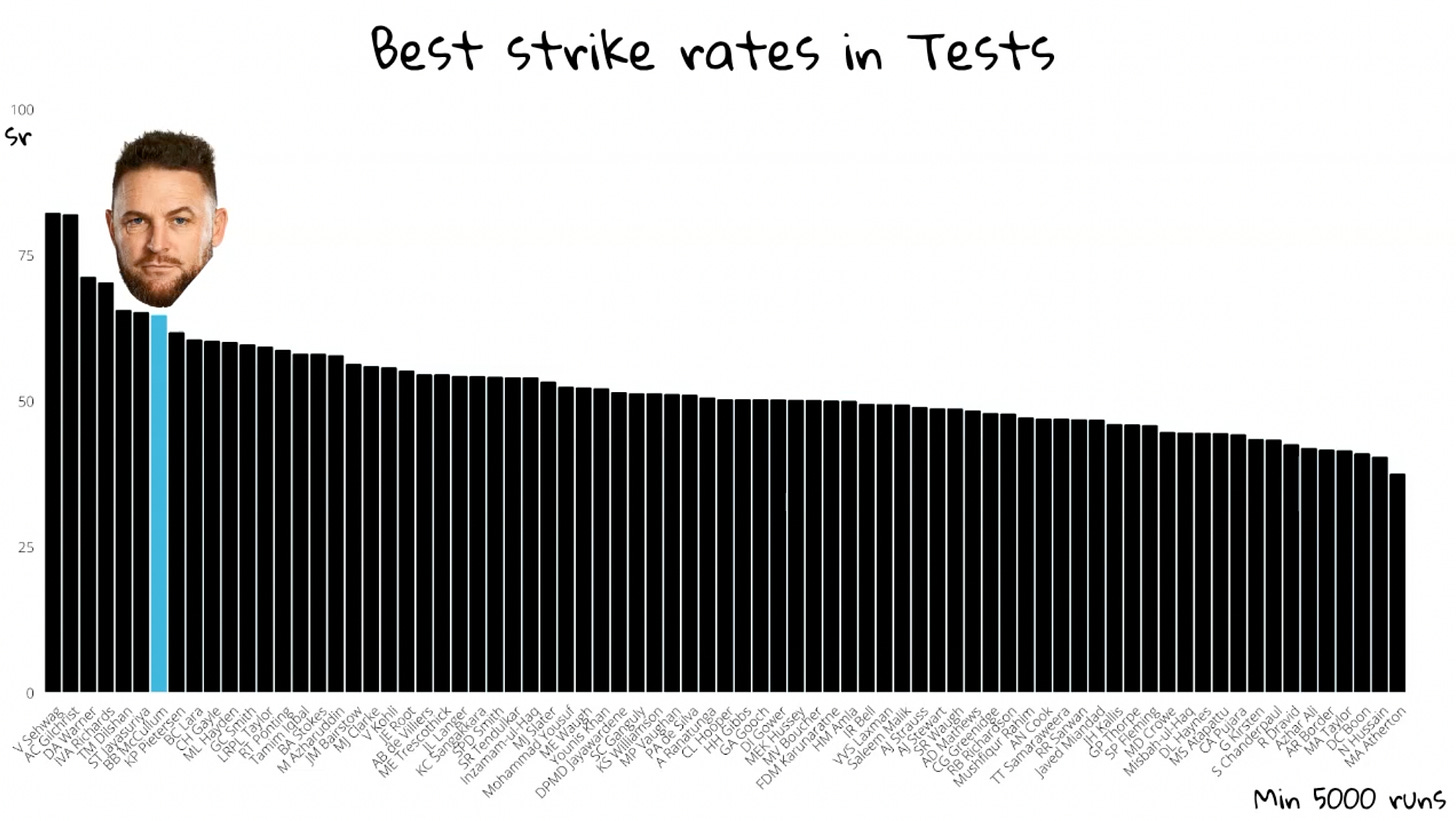

Bowlers are the attackers in Tests, so McCullum flipped that as the best strikers do. But more often, it was the threat of Baz, than the reality of him. His actual strike rate was at the boom boom end, but it wasn't always full-on explosive like Sehwag or Gilchrist.

But McCullum showed that he was all in. He helped mould a New Zealand cricket culture that was in danger of splitting due to T20, and gave them a new identity as their off-field competence grew. He was probably given too much credit. But how could you not praise him, the man was flying.

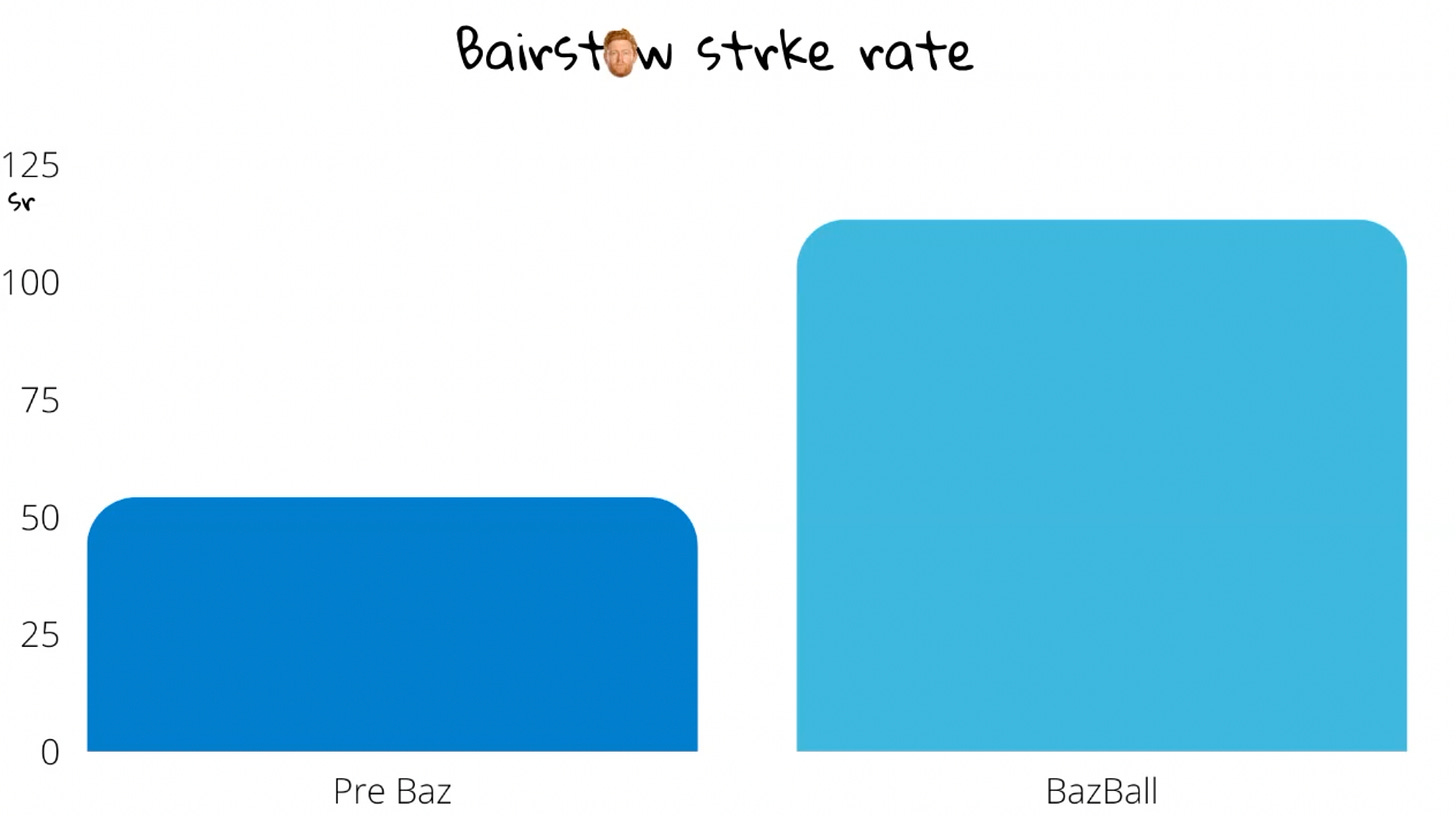

Jonny Bairstow has two hundreds scored at better than run a ball in Test cricket. They're both from the last two weeks. Under McCullum, his strike rate has raised three points in three Tests. And it's not just the notable knocks he has gone for it. He made 16 from 15 at Lord's, playing a few shots per ball. It just didn't work in that one. England have unchained Bairstow.

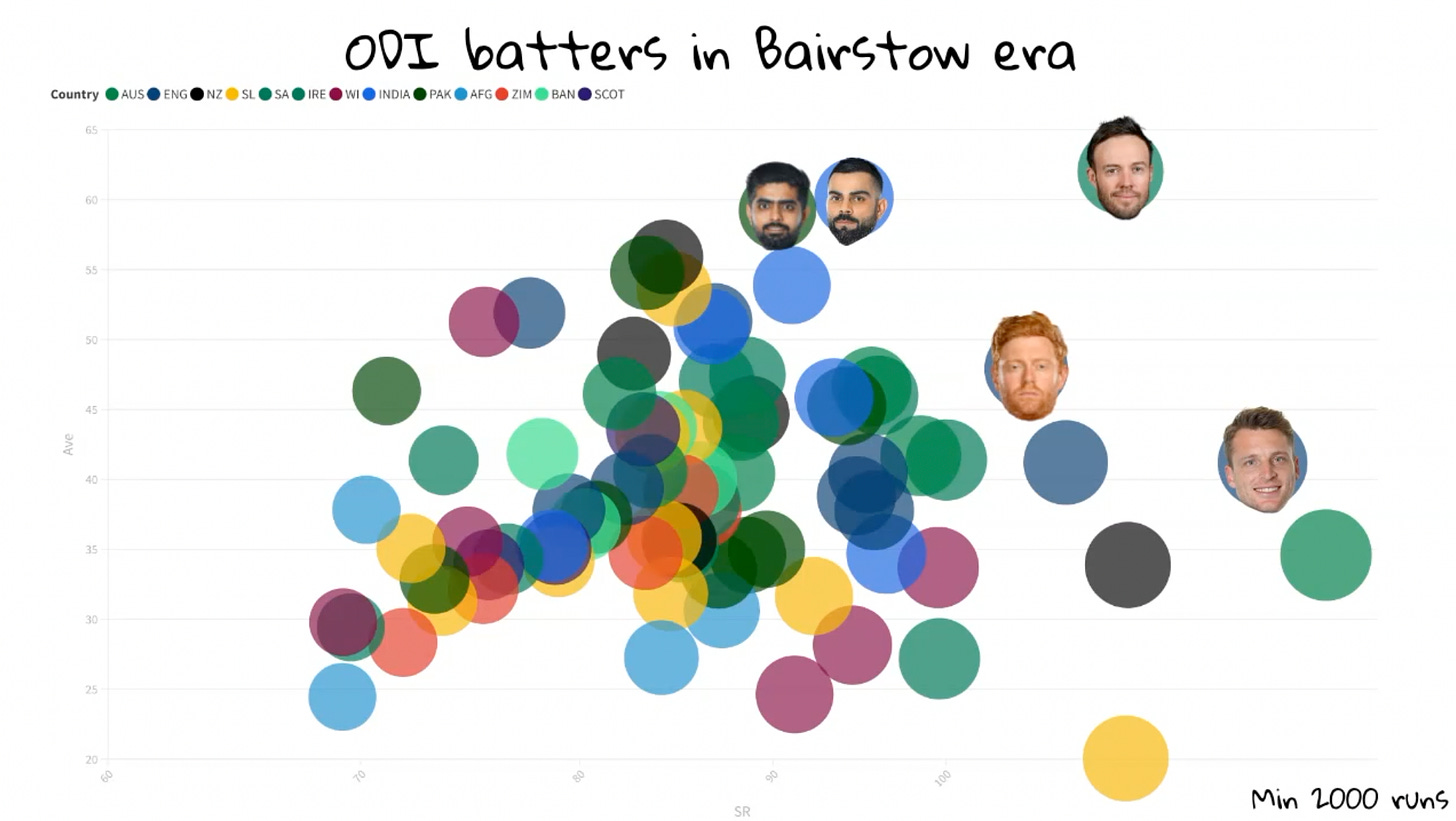

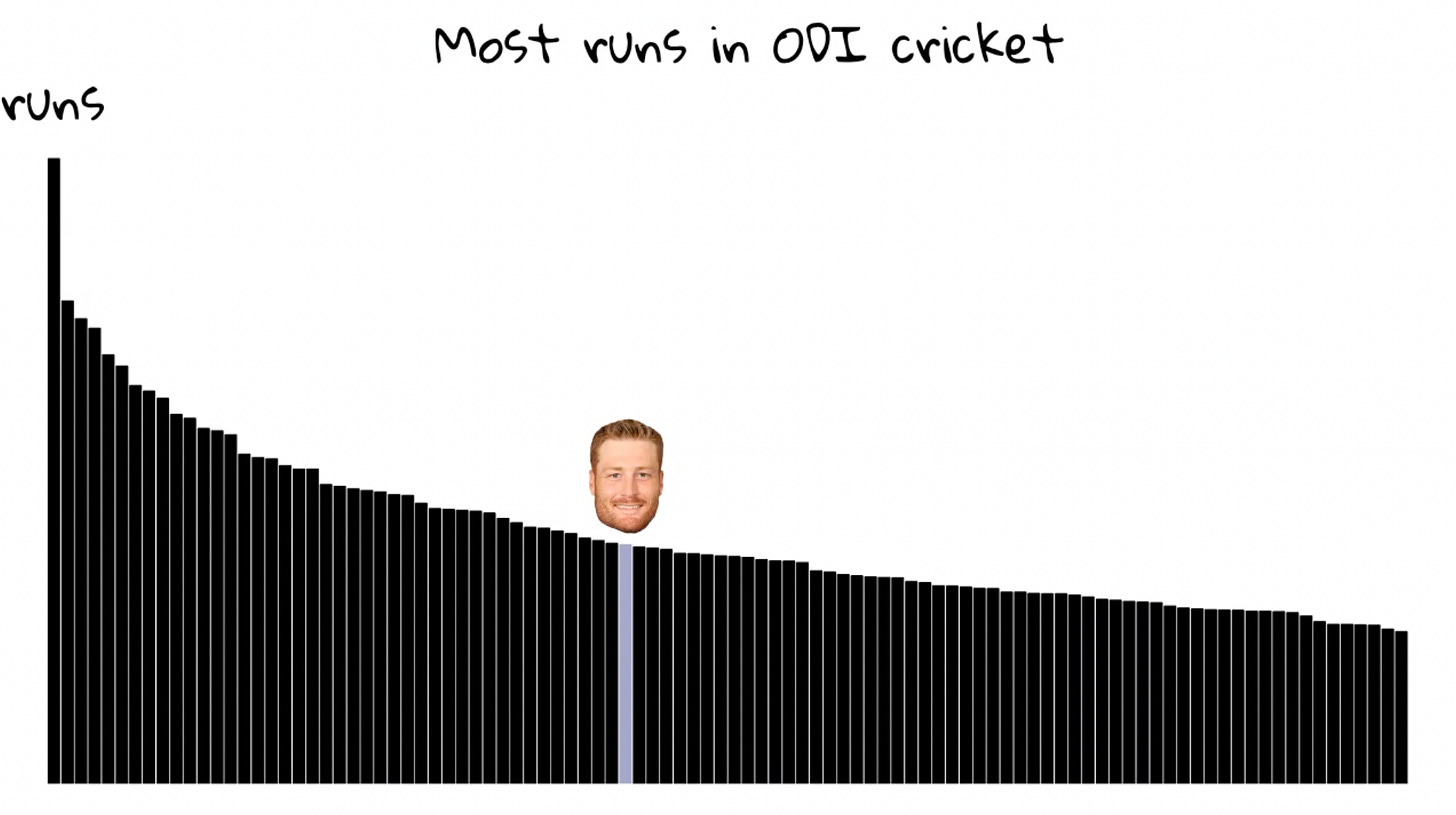

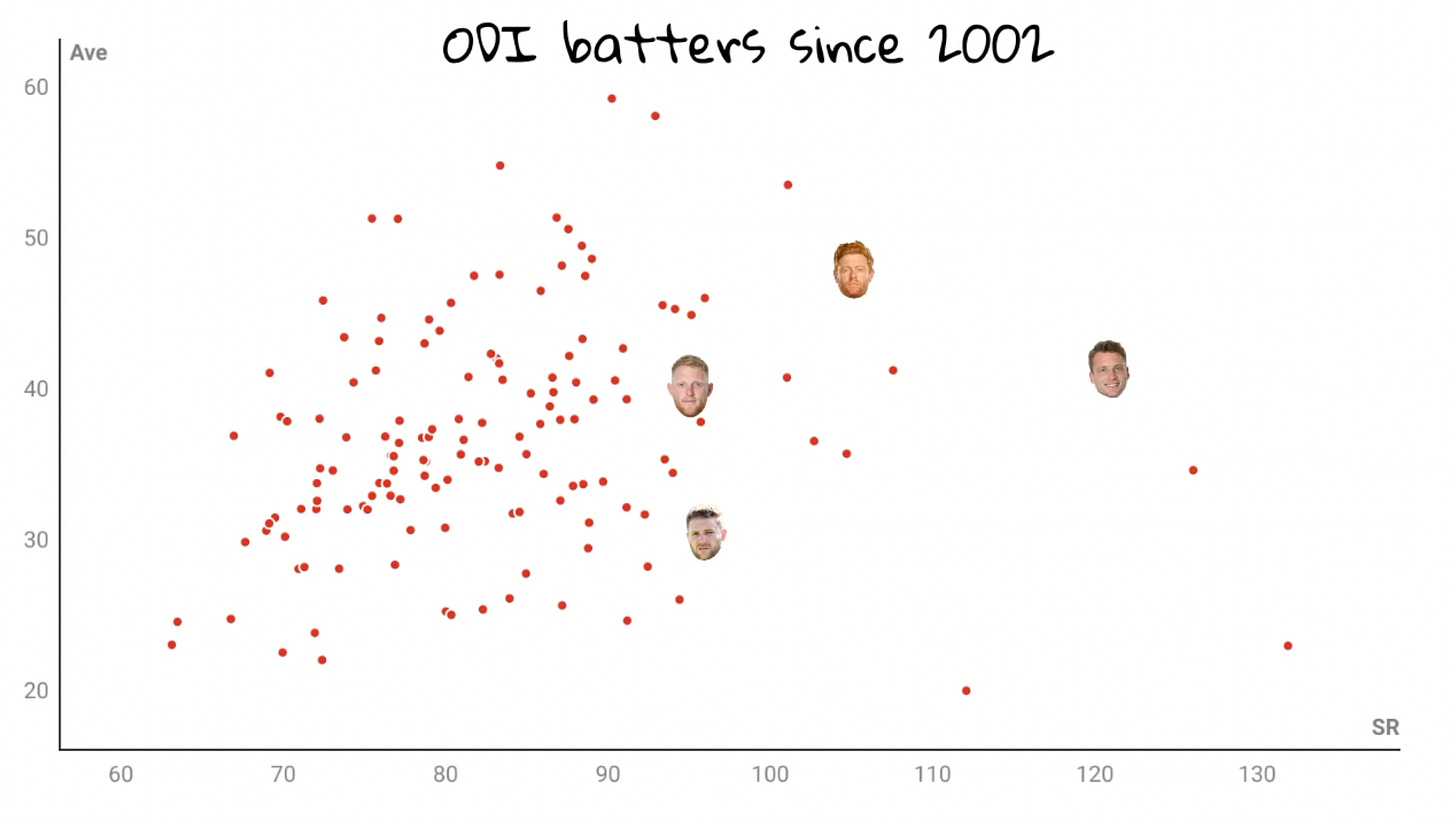

And we know what a free Bairstow is like. There is a Yuvraj Singhish ping off Bairstow's bat when in full flight. Like he's using a stick made of something more magical than English willow. In ODI cricket, he had to battle to get into England's team. He was an afterthought, yet this is him compared to the other ODI players during his career. Buttler is faster, Babar and Virat more consistent, and AB is just better.

But Bairstow is hangin' with the best players here. Averaging nearly 50 while striking at more than a run a ball. If his career continues like this in ODIs, then he's one of the greatest of all time.

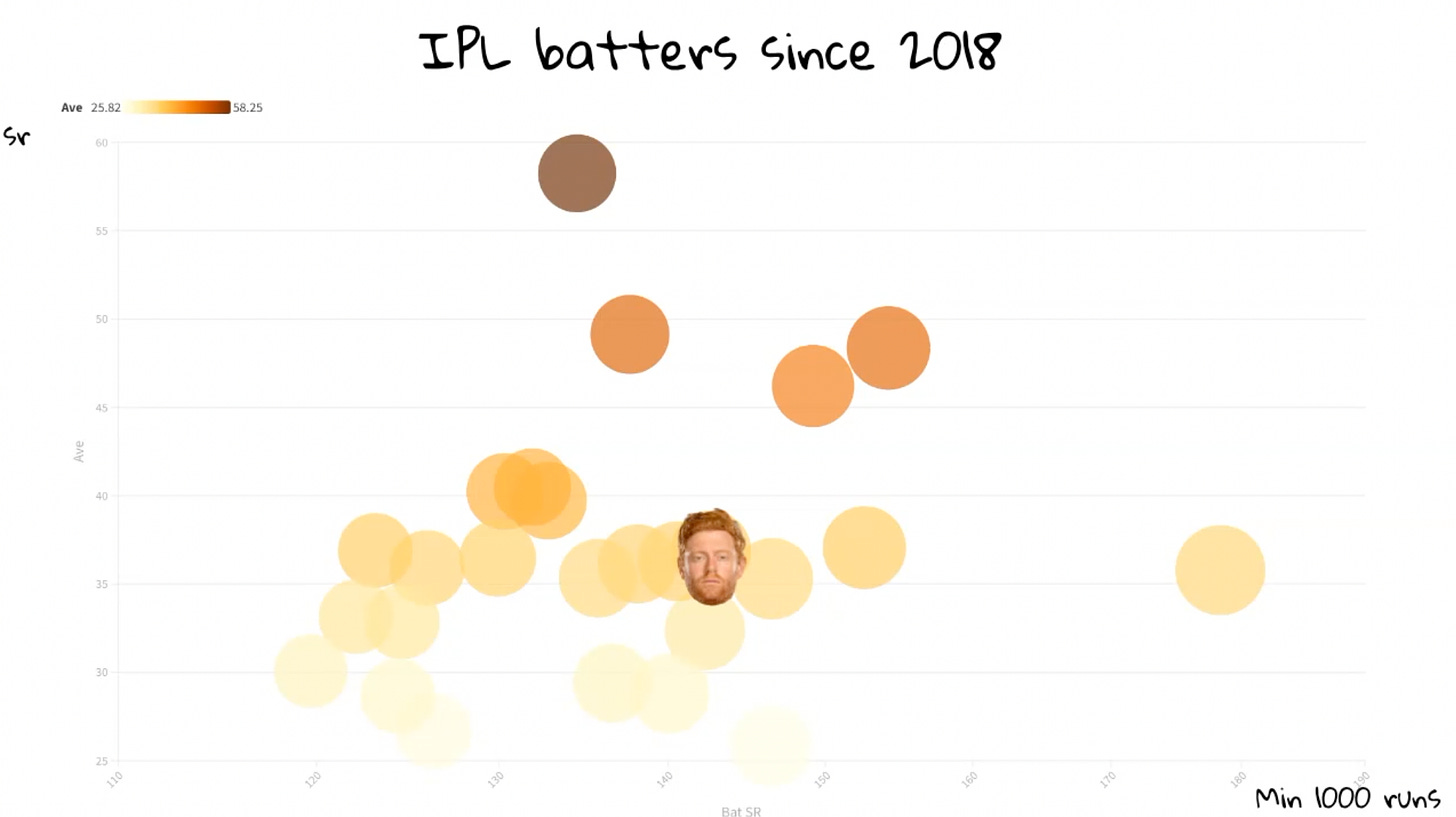

And he's obviously pretty good at the IPL. It took a long time for him to get there, and he exploded his first year. Then two poor seasons and two very solid ones. He's not been an out-and-out star. But he's at the right end with a good record.

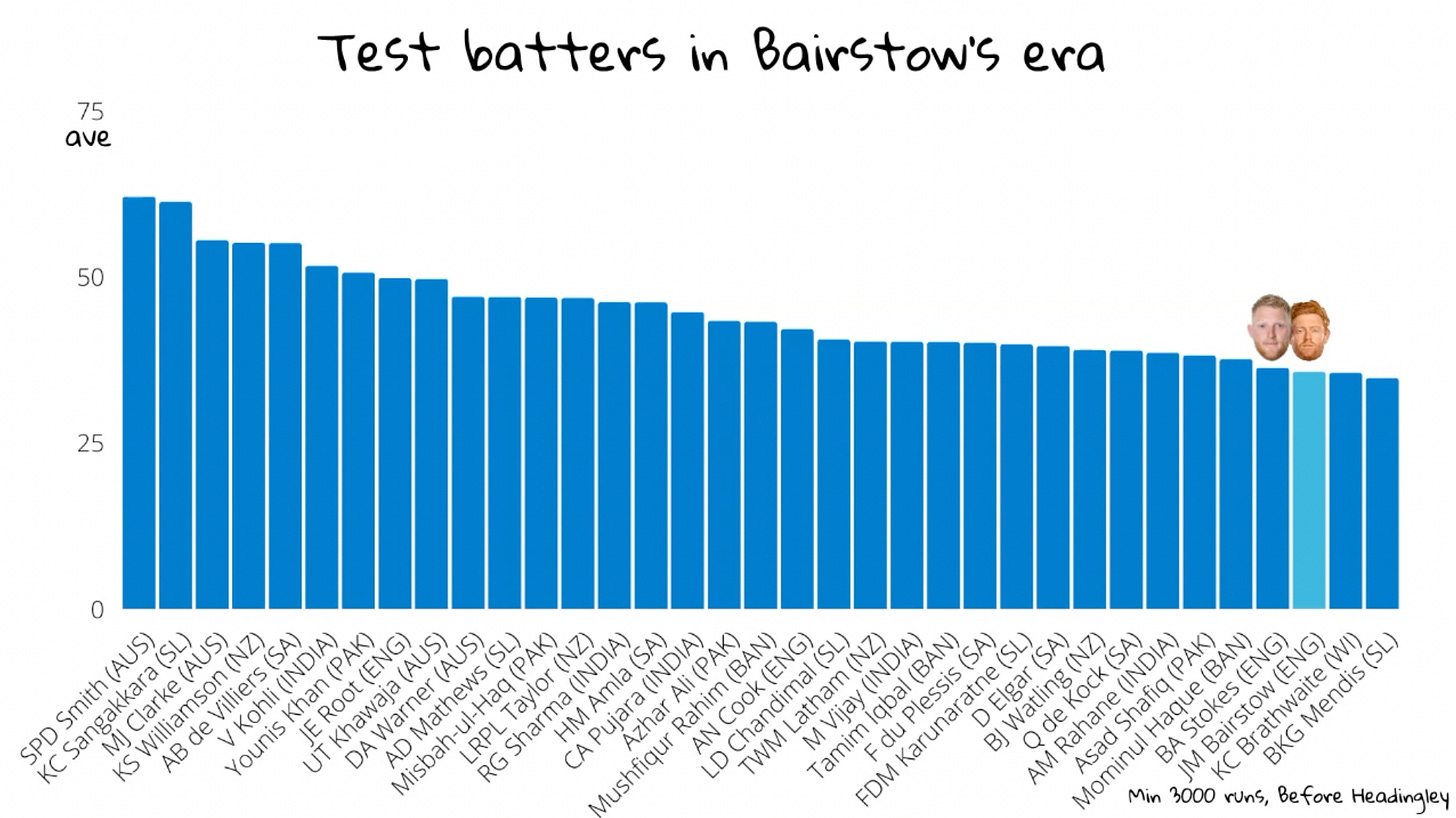

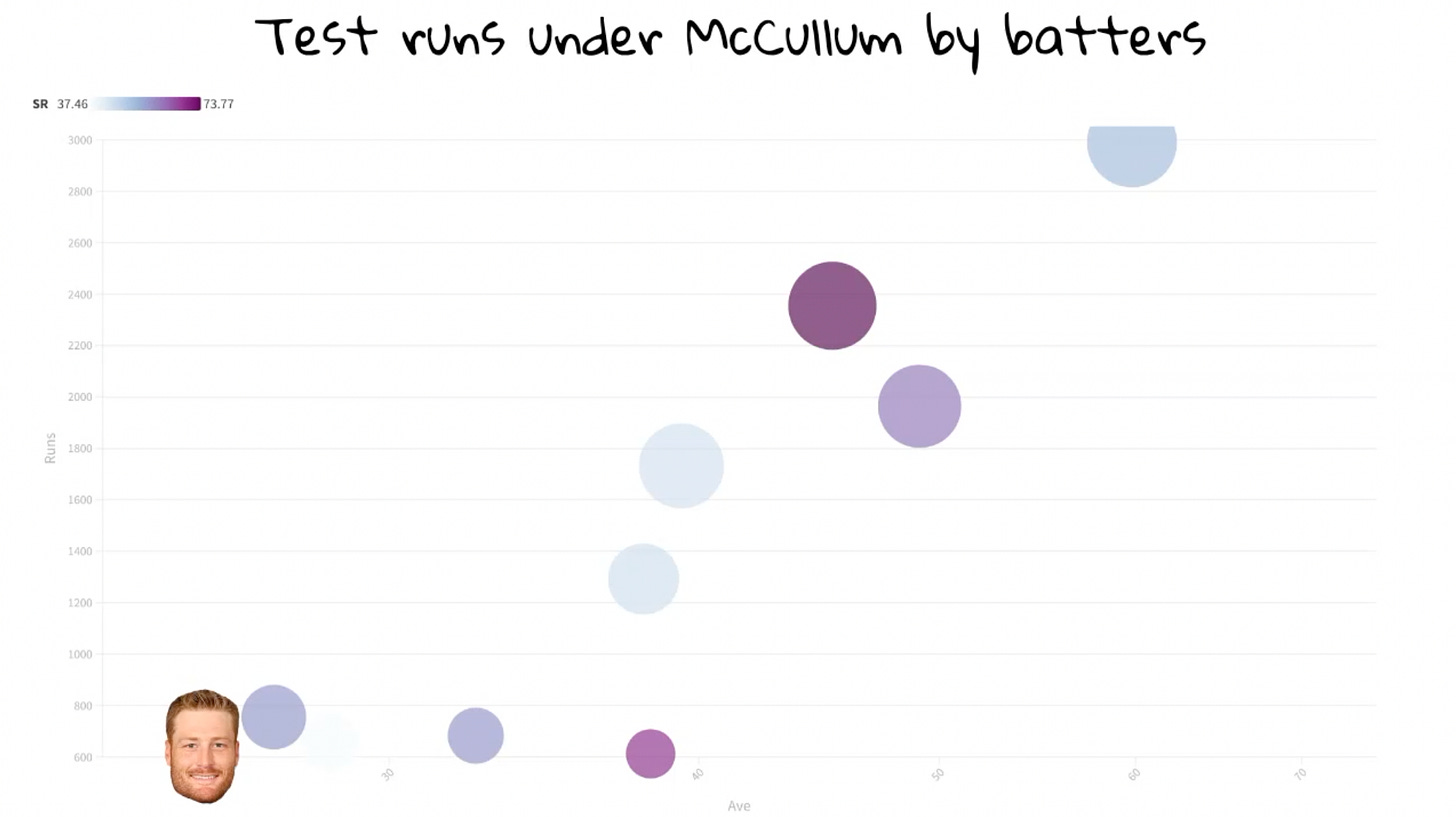

And then look at him in Tests. These are the guys with 3000 runs in his era. Down near the bottom.

It probably says a lot about England that he and Stokes are so low.

He was a keeper for a lot of this, but he averages more as a keeper. And ofcourse he has had bad treatment that led to a lot of this. If England wanted to ruin a player like him, one with incredible talent but also fragility, they nailed their execution.

You might also be thinking that Bairstow is just a white ball talent, which is why it hasn't translated to Tests. But he's been a gun for Yorkshire, averaging 50 over his career and having periods where he completely dominated.

And again, he did that as wicketkeeper. Bairstow could play red ball, we had seen flashes of it, but now we're seeing an explosion of it thanks to McCullum.

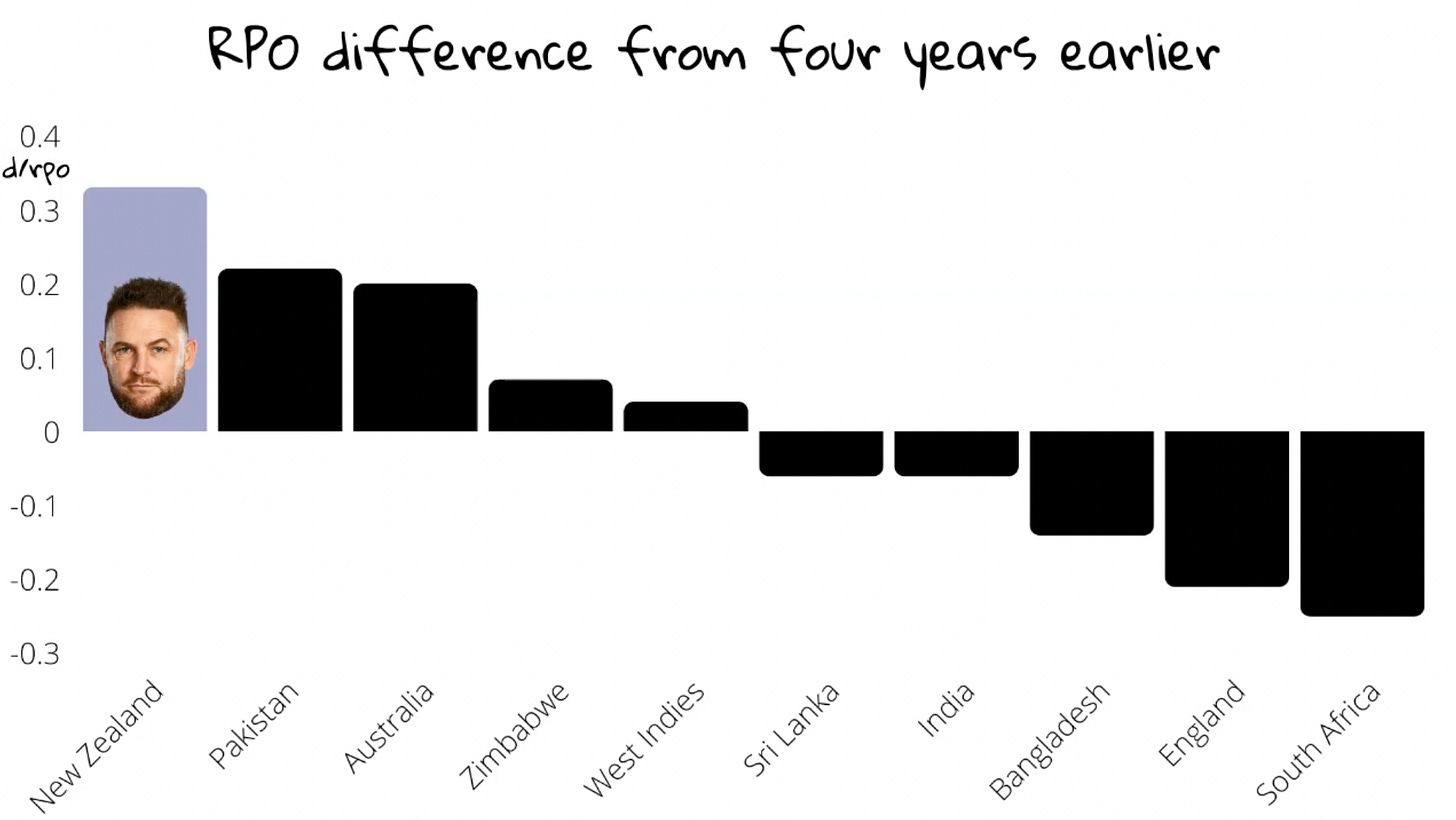

This is obviously the second incarnation of Bazball. The original was in New Zealand, where he took the captaincy - fairly aggressively - from Ross Taylor. In the previous four years the Kiwis won 6 and lost 15. With him in charge, their record was 11 and 11. Ofcourse many things changed, and they assembled their greatest ever seam bowling lineup.

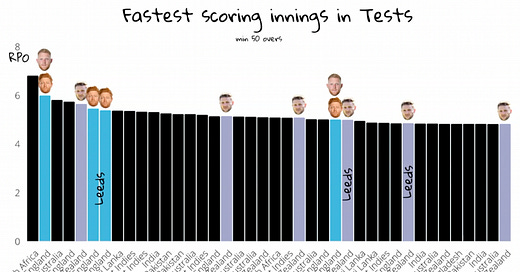

But batting wise, they were much faster.

Their runs per over were 3.4, good enough to be the second quickest in the world. You can see that most teams were hanging around three, so this was good.

It was quite a leap from the four years prior. And it wasn't just batting. It was fields, changing plans, and getting the players to commit. BazBall was a lifestyle choice. And McCullum was just as happy to boost up BJ Watling blocking as he was looking for players to smack it. It was about intent, invention and commitment.

He was happy to fly and let them be the best version of themselves.

But he trusts attacking players more than most because that is his people. However, backing white-ball batters without consistent runs in first class rarely works. David Warner is often pointed to, but he was different. He hadn't actually played much red-ball cricket. When he did, he made quite a few runs.

Of recent times we have seen Jason Roy, Alex Hales, Jos Buttler and Aaron Finch. All players were averaging in the mid 30s or lower in first class cricket. Roy, Hales and Finch all played in domestic red-ball in the middle order. Then they were given new roles at Test level based on their white-ball form. None of them made it work. Perhaps Buttler was the closest. And that is because he was in the same role as he did domestically. On top of that, he started as a specialist number seven bat, about the comfiest position in cricket. And ofcourse McCullum thinks he can rehabilitate him.

Weirdly, if anyone was well versed in how this could go wrong, it should be McCullum. His opening bat was Martin Guptill. In fact, he's a more striking example than the others. Guptill has 7000 ODI runs, averaging over 40, striking at just under 90.

The man destroys white balls. And he's not even a bad domestic red-ball player. Whether it be county cricket or back home in the Plunket Shield, he has a really good record.

Yet these are the specialist batters who made over 500 runs while McCullum was captain. And here is Guptill right at the back. It is not even close. He was just never got it right. And while he was slightly better than this over his entire career, he never averaged over 30 in Test cricket. So if a player of this quality can struggle, it does show you it's not that easy to take smashing blokes in white-ball cricket and make it a thing in Tests.

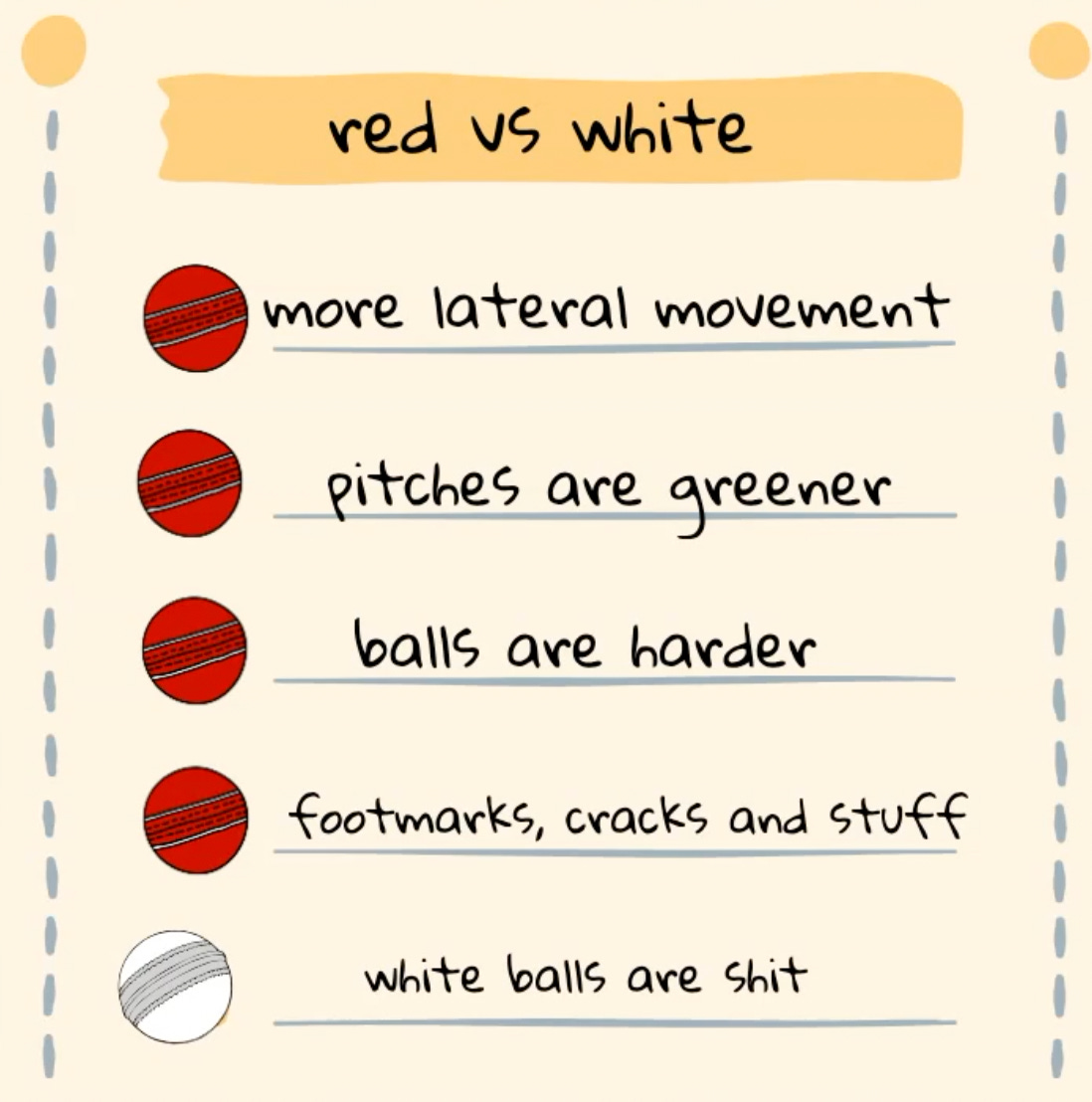

The balls move laterally off the seam, swing longer, and stay harder. The pitches are also not made purely for runs, they start greener, footmarks and cracks play a part, and the surface degrades. The same basic skills are needed for both, but they are different enough that it won't work for everyone.

It's notable that in this series that England has chased, the balls have become soft, and the wickets haven't degraded. Add in New Zealand's injuries with wacky selections, and things have been in England's favour a lot. They might be trying to change how cricket is played, but they're getting a breeze at their back too.

That doesn't mean England isn't going to change the game, or at least their own. Because this already looks better than folding for under 150 every match. They were already crashing; they might as well try flying first.

And maybe test cricket does need a refresh. Despite all the logical reasons teams don't play in Tests like white-ball cricket, so many people ask me if a team should try it. And with analytics and money, many sports are changing.

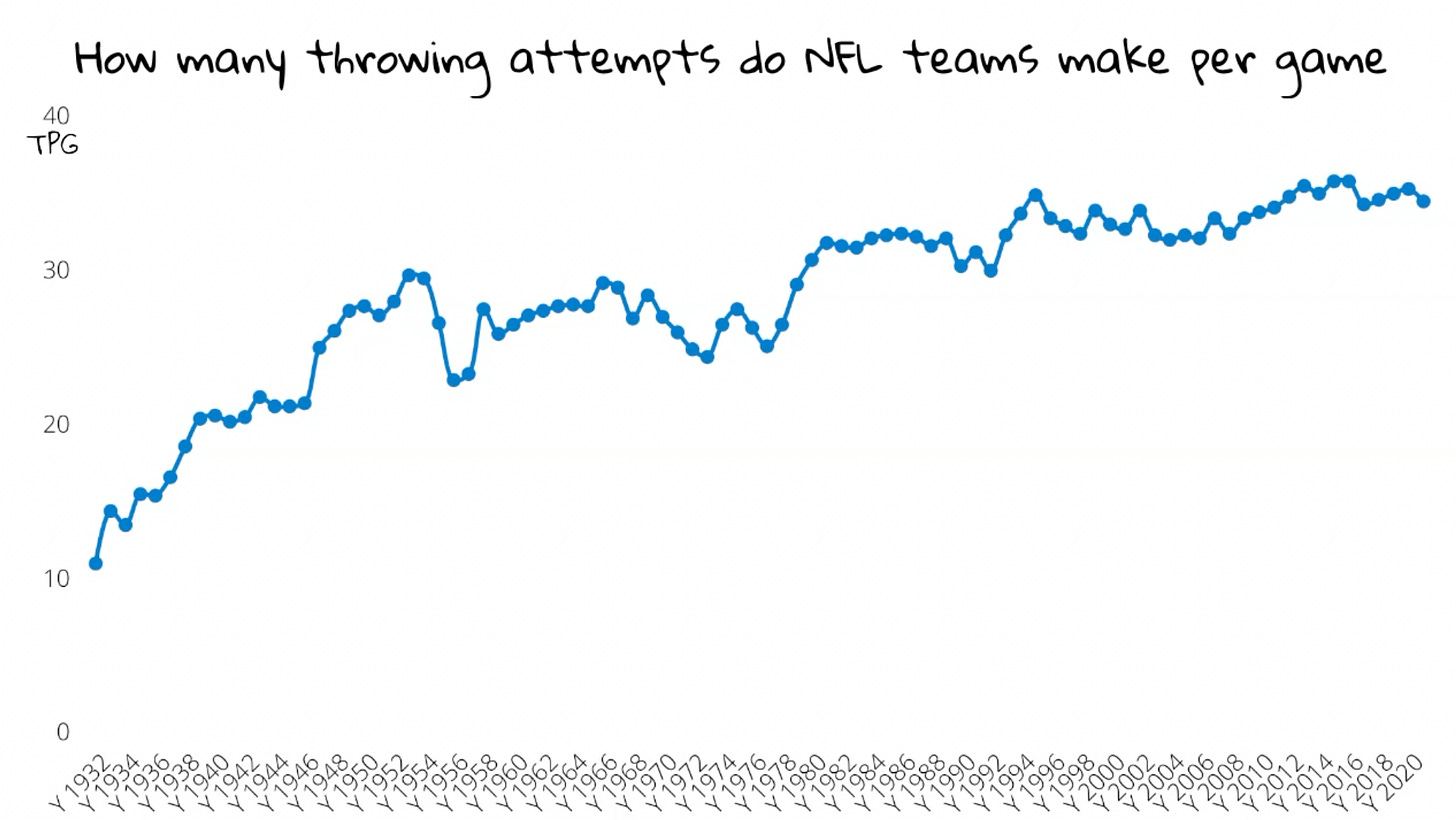

As a player of Madden video games and occasional watcher of NFL matches when I was young, I never understood why teams ran the ball so much. For two reasons, one, the players never got that far. And two, it seemed the same players were used repeatedly, meaning they had to get worn out by the constant contact. But I didn't know anything about the NFL, so I figured sport's first billion-dollar baby knew something I didn't. But since the year 2000, teams have thrown a lot more.

Now I wonder if they were just stuck in an old way of looking at the game and protecting the ball. Because they have started to throw it more, they have started to get more yards per play.

Lots of other things have happened as well.

Like the fact that people started calling the NFL basketball on grass. This was because when the quarterbacks started throwing the ball in the air more, coupled with extra spacing and non-stop movement. It meant the sport was more like basketball with its one-on-ones and constant movement.

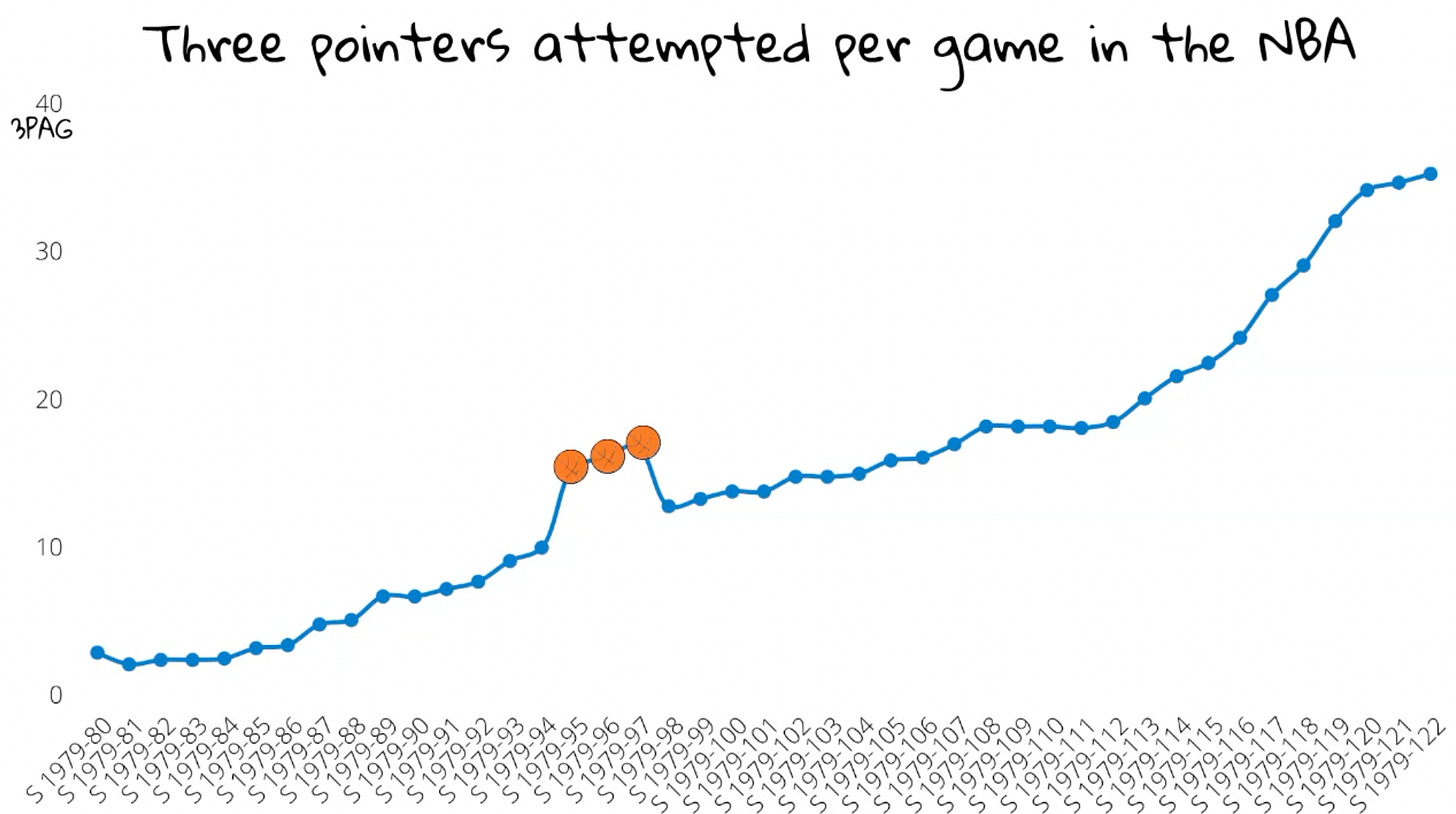

And basketball had its own revolution. When the NBA was merged with the old ABA, that lead to the three-point line. Which had a slow start, but then over the years, you know what started to happen, teams worked out that three points were worth more than two. It was a risk worth taking. But the players had to adapt as well.

(This little blip in the middle was when they moved the line closer.) But as you can see, teams have gone all-in on this.

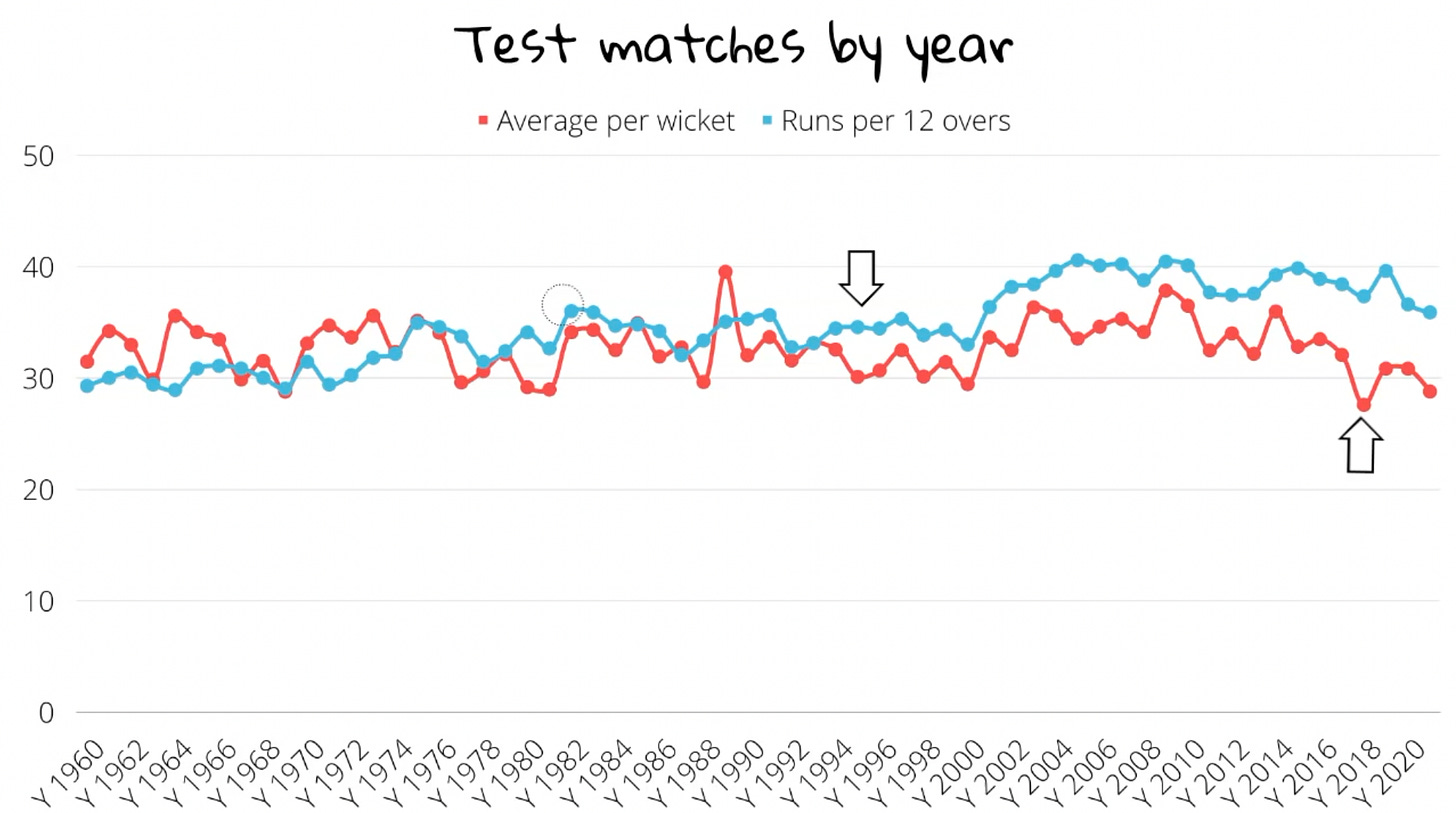

In Tests we had a change too. Runs per 12 overs and average for each wicket spent 30 years following each other pretty closely. But when ODI cricket began to be taken seriously, and Australia inspired some faster scoring, Tests got quicker. Instead of averages going down, they went up.

They are still high historically, even if they've had a little slide.

My favourite year is 2018, when the pace playing pandemic starts, no one makes any runs, but teams still score quick. Since 2001, the only year under 36 runs per 12 overs is 2021. In history there are two years before 2021 where we had 10 Tests in a year and broke that mark. 1982 and 1921. Now it's almost every year.

So with the modern sports where the scoring has got faster, it usually means it's with more risks, and therefore more variance between your results. So sometimes it works, and sometimes it crashes and burns.

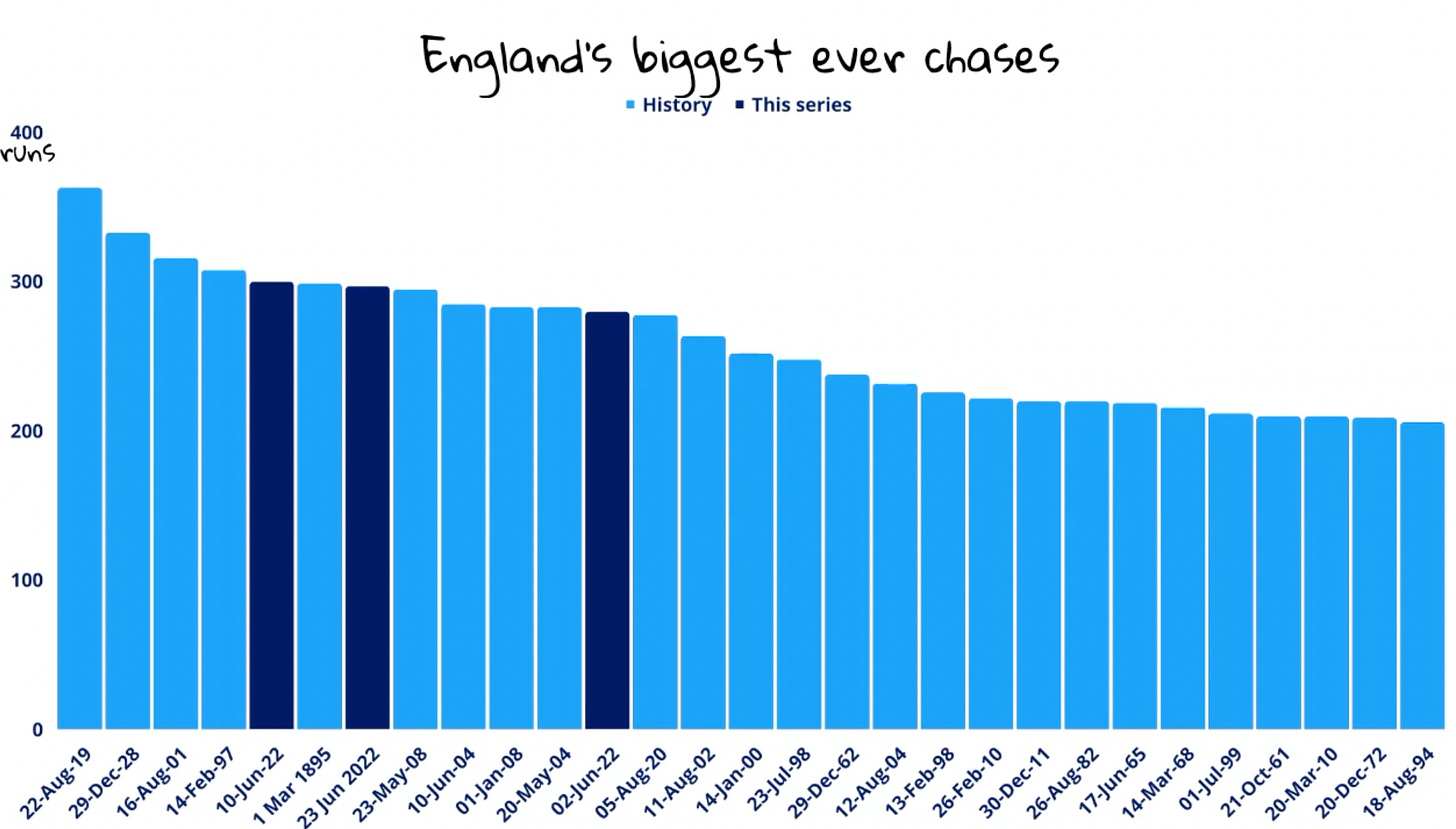

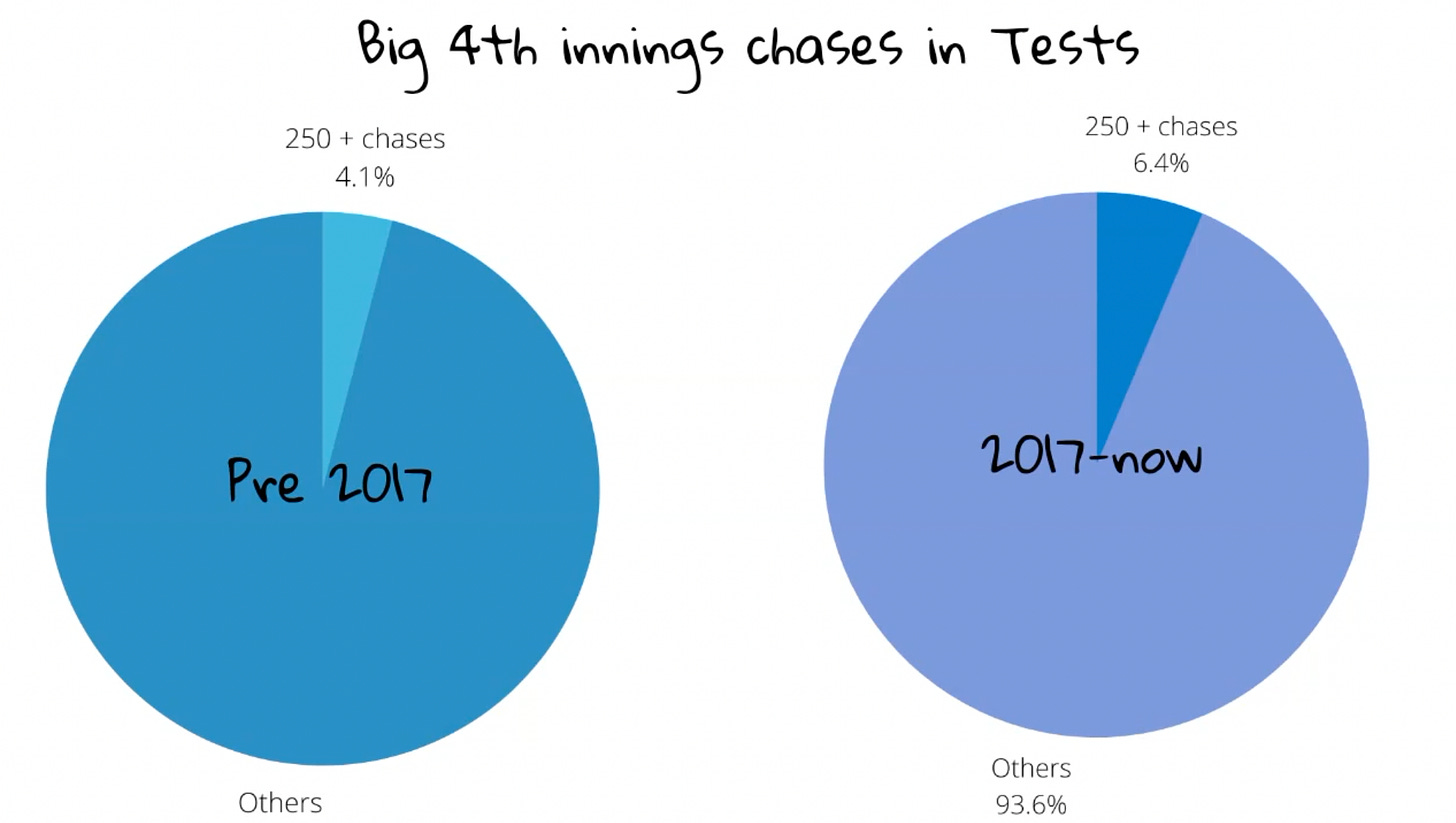

So it's worth looking at fourth innings chases. Before 2017, in less than five percent of fourth innings did a team successfully chase 250 plus. And you might think that happens all the time now, thanks to the last two weeks plus Ben Stokes and Kusal Perera. And years after people predicted this trend - due to how teams chase in white-ball - it has finally started to happen a lot more.

Since 2017 it's more than six percent, and it was happening more frequently before England did it thrice in a month. But they have taken it to a new level. So chases are easier now. However, that's happening at the very same time that no one can make lots of runs.

Test cricket has come to this: Teams are scoring less but chasing better. Some of this explains modern cricket. Because we have seen teams continue to score quick, even when they lose wickets. A chase of 250 no longer feels that much, even if 250 is still a fairly high score in cricket right now. And that's because you can do what Stokes, Perera and Bairstow have done. And if it comes off for a session, or even an hour, the game is over.

Welcome to the chase and collapse era.

It's worth noting that while it feels like England have been terrible for a long time, that isn't true. England weren't the world's best team from 2013 onwards. They fell off when Strauss, Trott, KP, Prior and Swann left. That is a lot of talent to let go of. But they went to a different model, one that involved a lot of all rounders.

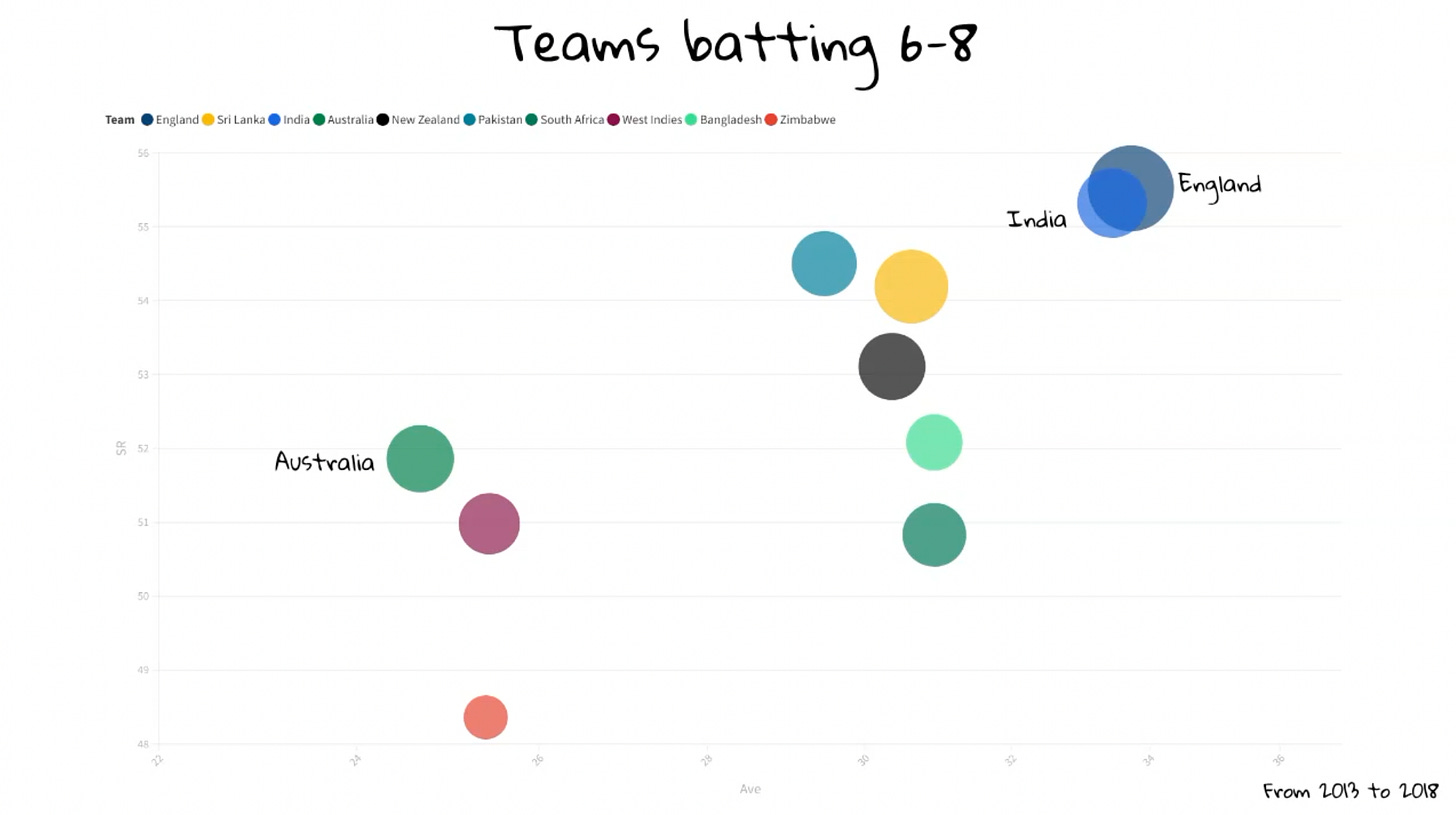

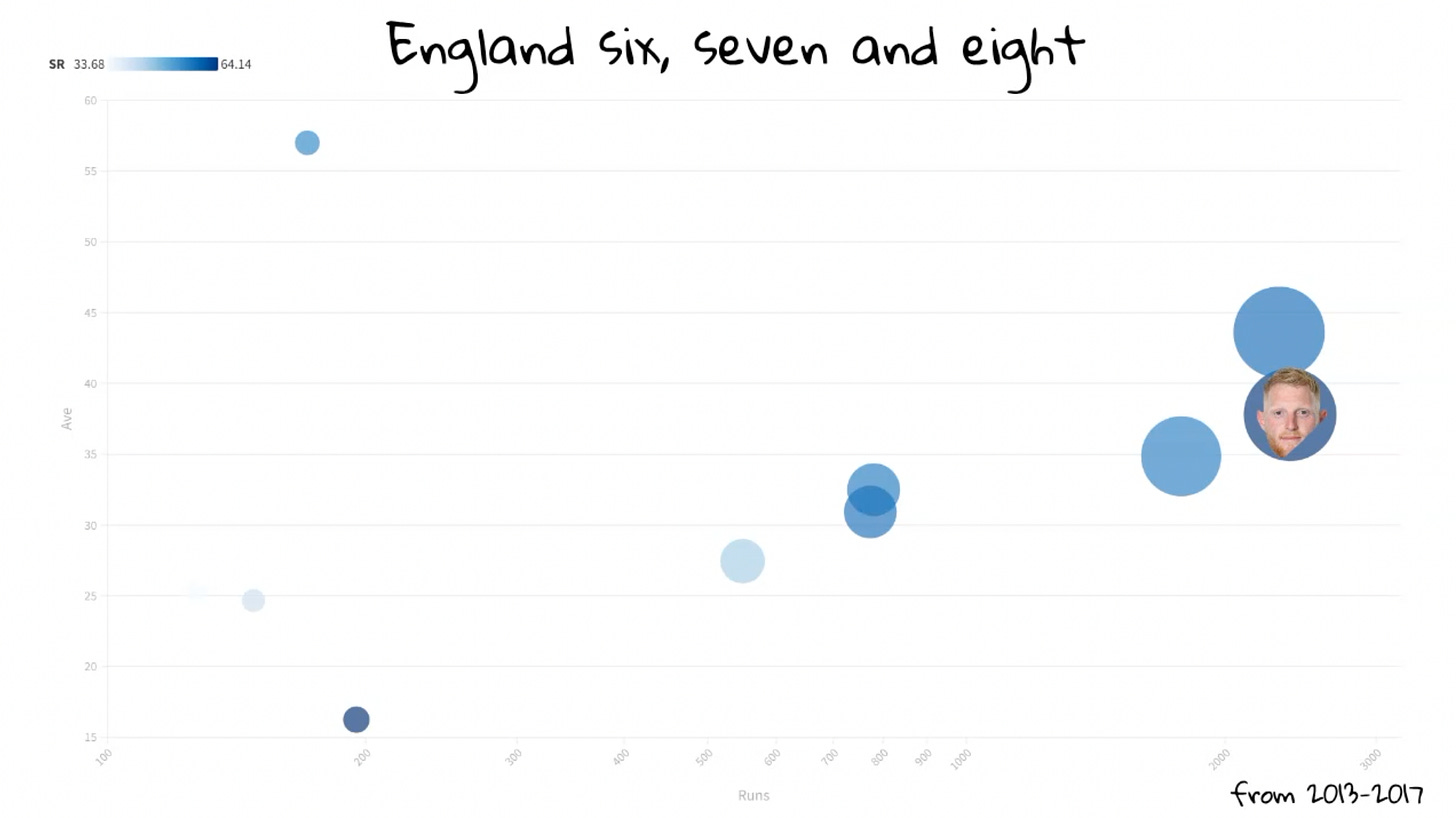

The top order they tried to fix with every able body around. But the lower middle was a real strength. They had the highest average and best strike rate between 2013 and 2018, batting from six to eight. Only India were anywhere near them. Australia are were miles off.

This fell apart when the Buttler experiment ruined Bairstow, Stokes had to go up the order, Woakes couldn't take wickets overseas and Moeen's batting slipped before retirement. Also, as the top order got worse, these guys were in too early, too often.

But at its best, the combination of Bairstow, Stokes and Moeen were incredible. Stokes was freed up at six to have a smaller load, and more break after bowling. Bairstow at seven meant he was playing the older ball and Moeen had the freedom to swing away at number eight.

Three players with all round skills, so less pressure on their batting and they made a lot of runs in this period. All of them had decent averages for their spots. England played entertaining and inconsistent cricket in this time.

Moeen Ali might not come back, but if he does, you could play him straight at number seven now, and let him bat how he sees fit. But they can replicate this somewhat by having Stokes at six, and Bairstow at seven. And they can add Harry Brook at five, another attacking player, though his first class record is a bit shaky. Or Buttler at seven, but as a specialist batter and let Bairstow bat at five as a keeper (if he is happy to do so).

They have options to bring back the core attacking lower middle order. But for that to work, they still need more of a functioning top. Kumar Sangakkara suggested Jos Buttler for that today. I don't think it would work, but it would be lots of fun.

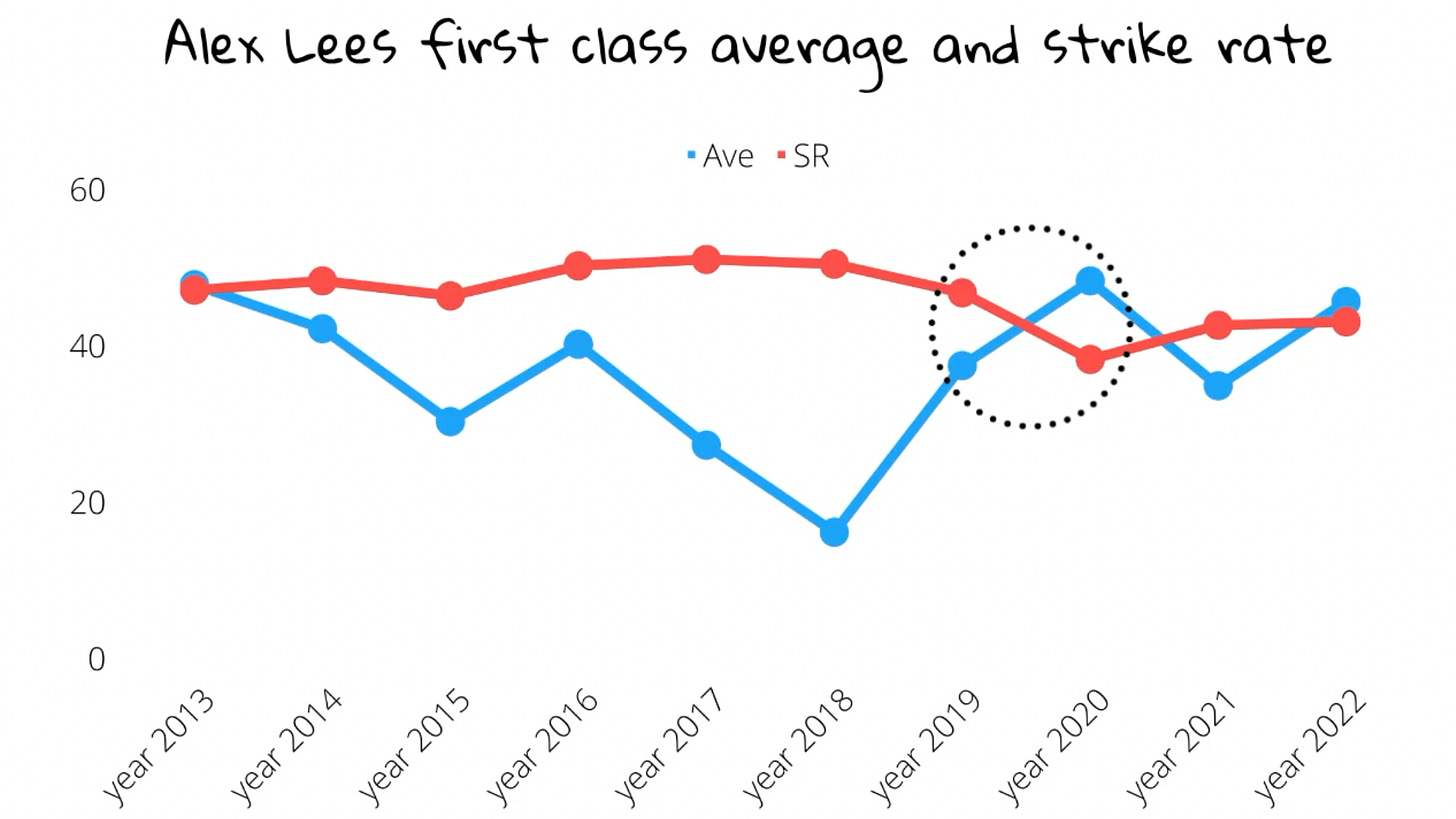

The top is worth discussing though. The most apparent impact of Brendon McCullum would be with Bairstow and Stokes. But Alex Lees is quite interesting. It looked like he would never make any runs in the West Indies, and he did that slowly.

He has been far quicker here in England. Striking at 50 isn't massive, but there is something here.

Lees has had a weird career. He started in 2010, but got proper playing time in 2013 and then stars. In the middle of his career he starts to drop off. These are some awful years. That is when he moves to Durham, and gets really defensive.

You can see that he kept scoring at the same rate until he rebuilt his game, and found some form while slowing down. Now maybe he needed to slow down to make more runs. Still, more likely there was a natural slowing when he changed his technique. The positive mindset he always had was replaced because this new way was working. But the fact there is a Baz bump is worth noting.

On Sky, Kumar Sangakkara talked with excitement at what England and McCullum were doing. The idea as he saw it was to get batters back to how they played when they were young. When they dominated cricket. We've certainly seen Stokes bat like that. Like he's in an under-14 game and his main objective is to make people run off the ground and cry. But to see Lees attack more, is really interesting.

During the peak of McCullum's batting, there was a thought that he could change cricket forever. It was only a few former players. But they mentioned how McCullum could take the slips out of play, and being that is where most top order players are dismissed, that's quite an achievement. Think of it like the England off stump method, but with slogging.

What McCullum really did in the end was something related to that, but not quite the same. He follows Mike Tyson's belief that everyone has a plan until they are punched in the mouth. McCullum was down the wicket, outside leg, hitting sixes all over the place. Watching Baz in form was like watching the Tassie Devil.

Think about this if you're a Test bowler. You have your main plan, say back of a length outside off or full at the stumps. Then you have your main line and length to default to. There is always a second and third option to each player. You can also adapt to the pitch or what the ball is doing. These are all normal bowling habits with a red ball. But Baz makes all those plans explode when he's running at you or backing away. And he can score at ten an over, or even more. That speed gets in your head because once McCullum is flying, it's too hard to stop, and there is an aftertaste that lingers.

That is what Bairstow and Stokes have done in their chases. New Zealand has been unable to curtail them bowling in a usual manner. And have been too slow to move into white-ball methods.

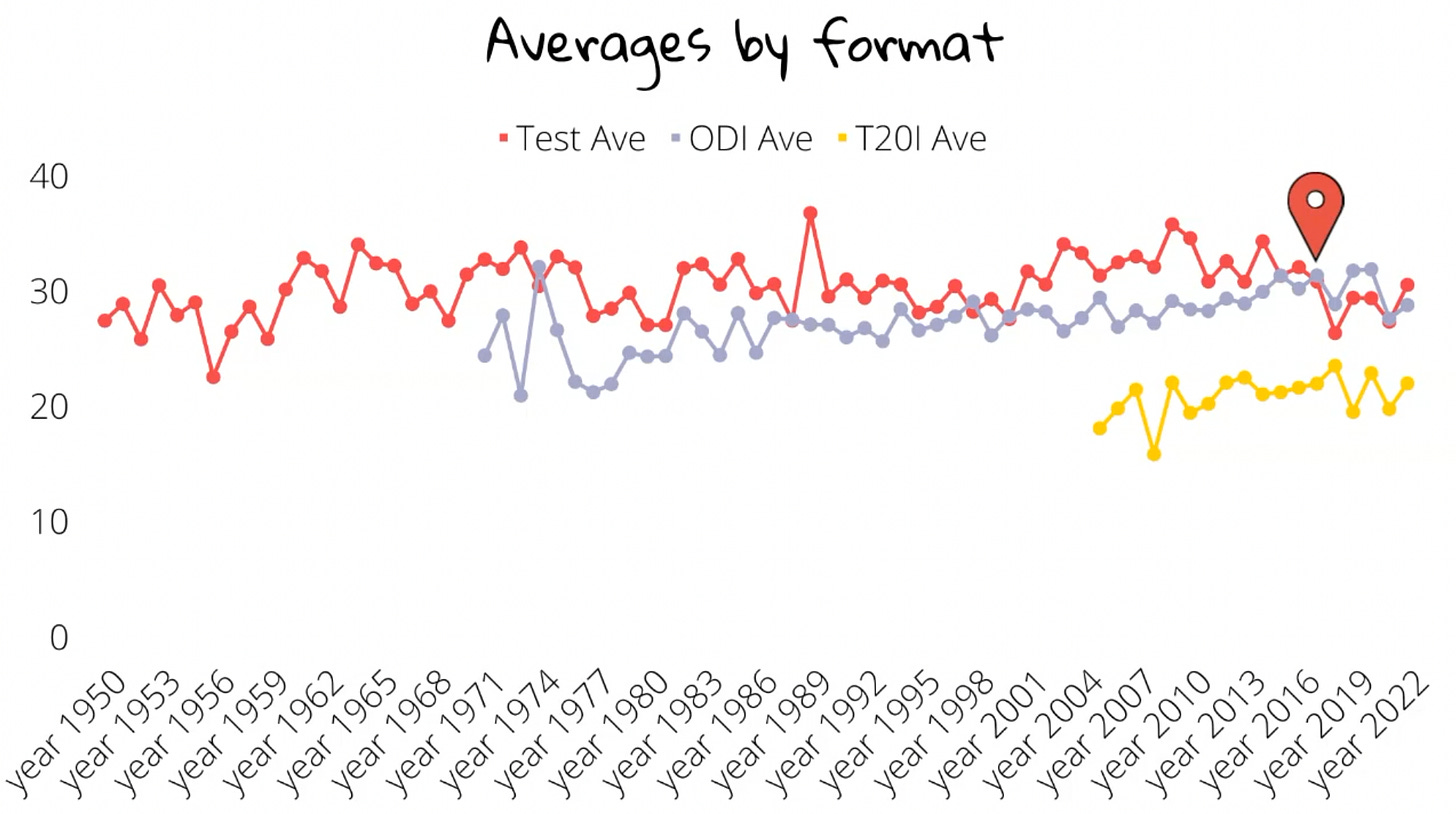

England's batting in ODI cricket - like the West Indies in T20 - changed batting. And while the last evolution in Test cricket was probably Australia's four an over idea in the 90s.

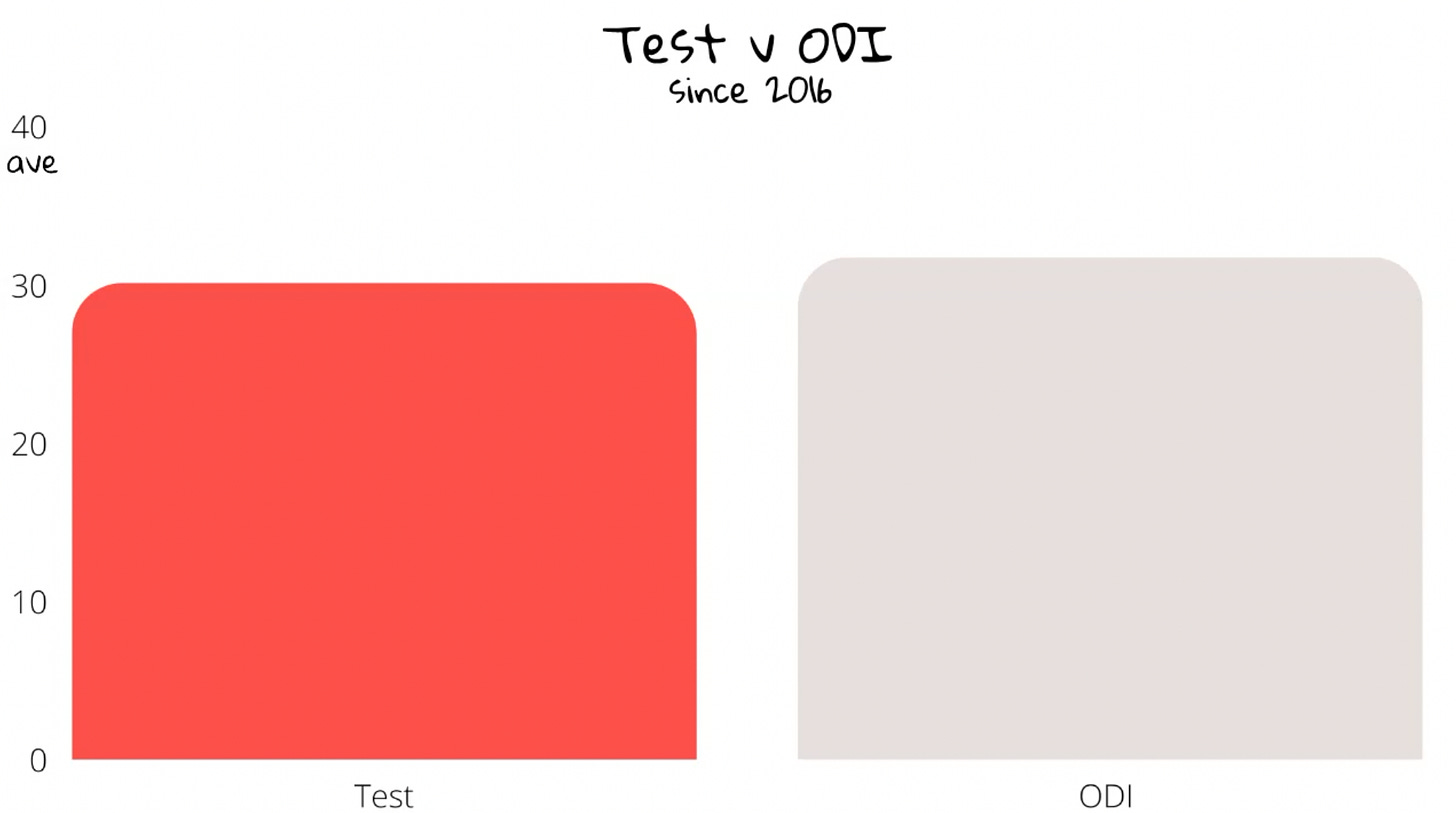

But that was before batting changed. The bats, the batters, the mindset, the training, and the shots. And I didn't show you this before, but I've done a podcast on it. In 2017 ODI averages were higher than the Test game for the first time.

Test v ODI (since 2016)

And it's not a one-off. The last few years ODI averages have been higher, just as the red-ball game has dipped.

So why not use that to your advantage. McCullum was trying to change batting in Tests from the middle, but he might have even more impact from the boundary.

Think about what happened with Neil Wagner and Joe Root in the third Test. Wagner was setting him up late for the wide one on the drive. He had packed the offside, and this was a tactic weirdly the Kiwis hadn't tried much. The commentators said he needed to be patient and Root would chase one.

They were right, but when he did, there was no straight bat that could be edged because he was reverse scooping. The field wasn't set for that. Why would it be? Root picked up a six, and there was risk in his shot, but perhaps not much more than a cover drive with a stacked offside field. And that one shot meant New Zealand had to find a new plan.

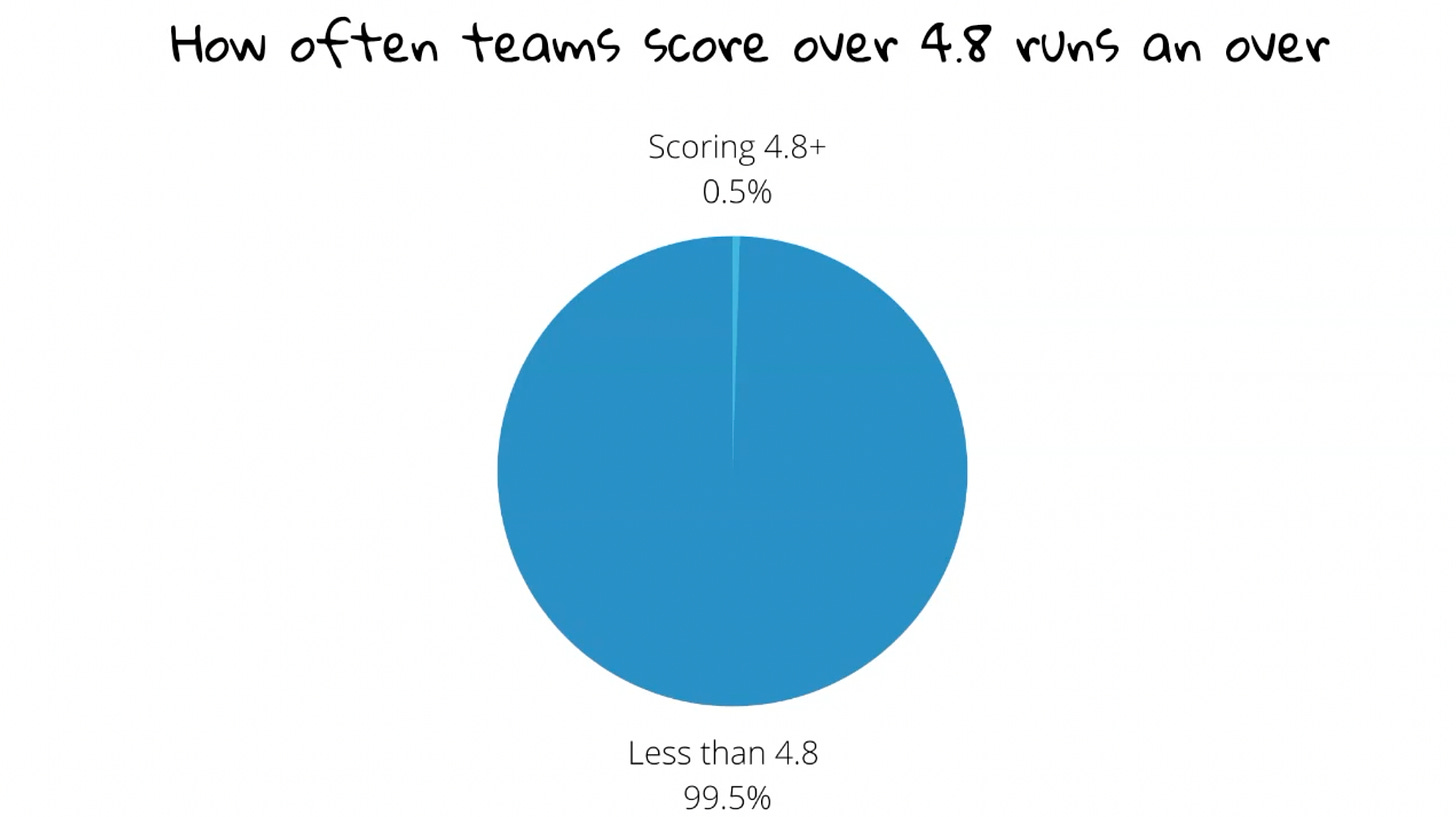

If you can't bowl dry, teams will score quick. So what does this look like in real terms? There have been 7602 Test innings of more than 50 overs. In those, only 40 times have a team scored at higher than 4.8 runs an over.

It's a hard thing to maintain in a Test match.

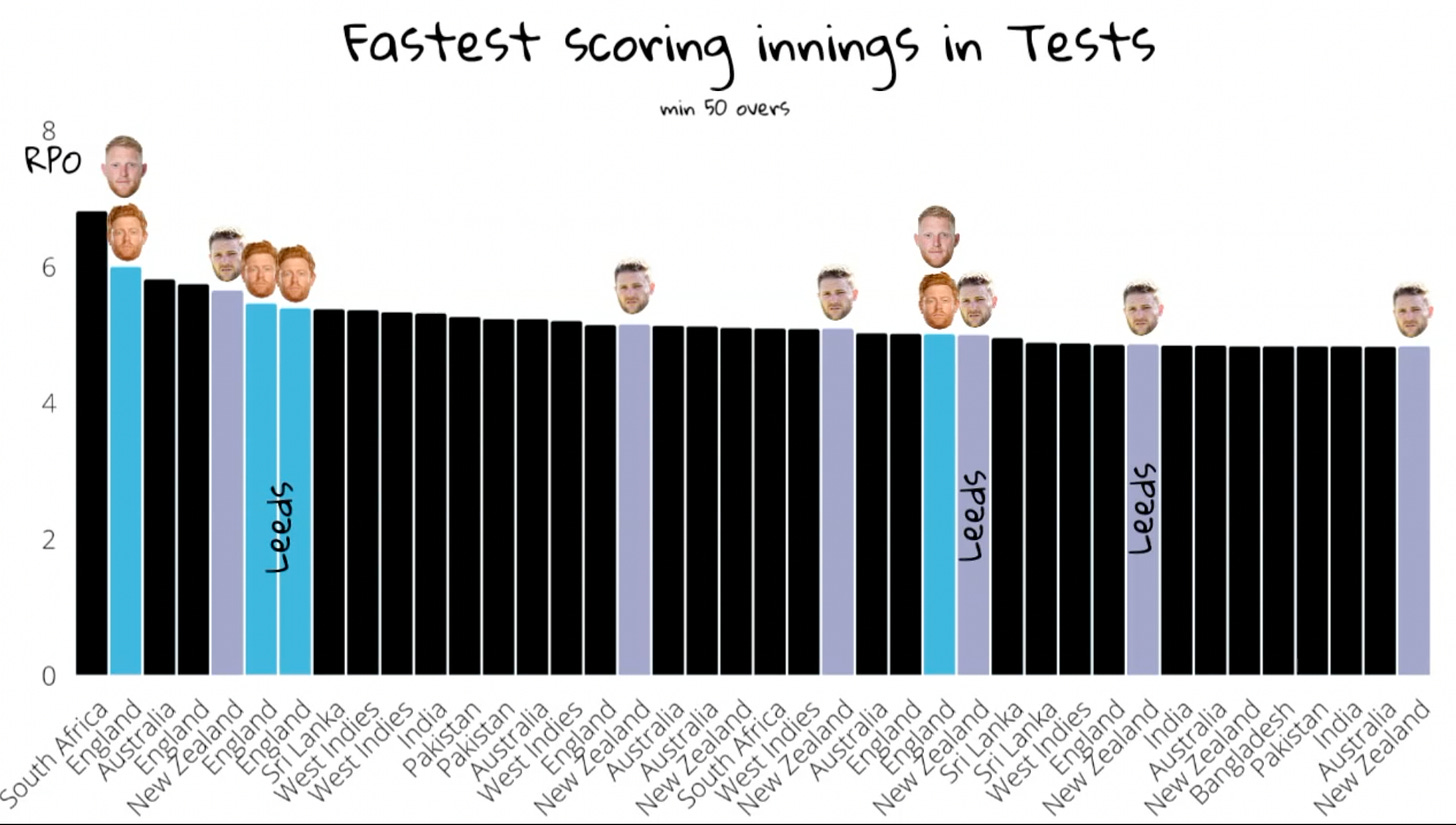

They are mostly modern day Tests, with only eight before the year 2000.

The ones in grey, those are the ones that McCullum made huge fast scores, or the two at Leed’s where he finally got his team to give it a go for him.

It was that match that was he height of Bazball in the UK. He had absolutely won them over by the time he did this in Tests. If they had rolled his ashes into a joint, English cricket would have smoked them.

But there is more here to enjoy. Because I have another colour highlighted here. The light blue are England, and the first three are from this series. I’ve put the head on the players who played a big role in these chases.

But they appear in another one too, their knocks in Cape Town of 2016 can be seen in the middle. All McCullum has done is allowed them to fly.

And the thing is, as Cape Town proved, they could already fly. In fact, if you look at their ODI records compared to McCullum, Stokes hits at the same rate, but from the middle overs with a better average. Bairstow beats Baz easily with average and strike rate. Obviously if you want - and England might - you could add Buttler.

And they have others. England have access to Moeen, who smashes it. The next batter in is Harry Brook, he has a strike rate in T20 of 150. And then there is Liam Livingstone.

None of these players are McCullum, he was a man unlike any others. But in England right now he has some of the most attacking players in the world. Guys who have changed ODI cricket forever by scoring at more than a run a ball. And quite a few big scoring IPL seasons as well. Their team is not always good, but they have been consistently innovative, for better and worse. And they are desperate to try something new. And now they have a man who they believe in more than he does himself. And a whole squad of batters who like to smash the ball. It seems like McCullum's plan is just to press the red button and see what happens.

And all we can do is sit back and see if the experiment works, or if they crash. When he played, McCullum was a player you had to watch every ball of. So far as a coach, he's the exact same thing. Welcome to Bazball.

Great article with good analysis - a really enjoyable read. I still think that Bairstow can't keep this up - especially considering the pitches are flat (mostly) and when England's top does collapse (regularly), then he will be exposed to a moving ball - if we remember how Bumrah dealt with him last year, I think he will struggle. Your thoughts?

At last. This is the first thing I've seen or heard which explains to me both how this revolution has happened and, more importantly, defines what the revolution really is. The analogy with Tyson's "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth" is brilliant. NOW I see what England are trying to do.

There were hints of this attitude in Sri Lanka, early last year, where Root got straight to the point, and swept and reverse-swept the Lankan spinners out of the game before they had a chance to implement their plans. Got his retaliation in first, if you will.

Indeed, after the first Test of that series, George Dobell offered the following headline:

"With Joe Root at the helm, have England fans ever had it so good?"

https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/sri-lanka-vs-england-1st-test-with-joe-root-at-the-helm-have-england-fans-ever-had-it-so-good-1248345

So, we've been having glimpses of Bazball before now - the door has been ajar for quite a while: we've just needed McCullum and Stokes to be given the word to kick it off its hinges.