EXCLUSIVE: The three wides of the Bangladesh Premier League

A long investigation into some BPL matches and two occurrences that are around 1000-1 and 2000-1 that happened after seeing some movements on the betting market.

This is a wide. They happen quite a lot in T20 cricket. But this was one of three wides in a row for the tenth over. Do you know how rare that is? We do, we checked.

This was on January 7 in the Bangladesh Premier League. Dhaka Capital made 111 runs after being 62/2. Collapses happen, and it wasn’t the only dramatic loss of wickets in the BPL that day.

But it meant the game was pretty much over, so even hardcore fans were probably tuning out after Rangpur Riders’ Alex Hales scored 44 from 27 balls in the second innings.

However, those wides happened at the end of the 10th over, and weirdly enough, that is the most important part of this game.

That is because a lot of money had been bet on the fact that after ten overs, the score would be more than 79.5 on major trading sites like Betfair. Some traders were betting large sums for what was only an even money chance while needing 26 runs off 12 balls (the line had come down to 78.5) with Hales at the crease. But after he was out, the runs needed were 18 from eight balls, with a new batter at the crease - and still they bet again. In the tenth over, more money came in for the score to be more than 78.5 runs, despite the fact that 12 were needed off four balls, there was a new batter at the crease, and there had just been two dot balls.

After 9.5 overs, scoring 78.5 was practically impossible. Because the score was 72 with one ball left in the over. But seven runs were scored from one ball. The people betting very big money despite the odds not being in their favour after dot balls and wickets were correct.

I am not accusing anyone of match-fixing. Legally, I cannot do that without evidence anyway. That would leave me vulnerable to being accused of libel and the laws in the UK are widely regarded as being weighted in favour of claimants. That is the case in lots of different places across cricket. So this piece will absolutely not do that. What it will do, is describe what happened.

I regularly get messages from fans telling me about matches that are fixed. It is usually a run out or two, or a collapse. They call this evidence, but generally, it is just cricket. Proving fixing is very hard from just watching a game.

You would need to be able to match a moment in the game with some kind of hard evidence. I don’t have access to players' phones, nor have I been doing an undercover sting.

This is not about proving match-fixing at all. It is simply showing you some things that happened in a couple of games, and then looking at what the betting markets said.

But first, I want to show how hard it is to cover a story like this. On January 7, there were two games in the BPL. In the other one, the Sylhet Strikers lost a wicket on the third ball. Former Bangladesh international Rony Talukdar was out trying to hit big. The odds on the match at this point were that Sylhet had a 17.5% chance of winning. A staggeringly low amount after only three deliveries had been bowled in the match, with another 237 to come.

It didn’t make any sense. Clearly, they had lost an opener, and Fortune Barishal was the better team, but with one early wicket between two fairly even sides, an early dismissal shouldn’t change the odds that much. Especially as Sylhet had plenty of overseas batting to come with Rahkeem Cornwall, George Munsey and Aaron Jones. Cornwall smashed Shaheen Afridi, then Munsey had some fun too, and they got the Strikers to 76/2 before Munsey was out. That started a collapse of 6/13, on the back of some quality bowling from Jahandad Khan.

The collapse was dramatic, but what I thought was interesting was how sure the market was of this happening. In the previous match – on a better wicket – the Strikers had made 205/4 in a losing cause.

But I watched this live, and the dismissals seemed absolutely fine. It was the odds that were weird. I talked to experts in the gambling industry about this game and the Bangladesh Premier League in general, and they said that many odds things happen in the trading of these games that often spook the market.

“We have had concerns about the BPL for many years as it’s the most erratic market of any of the ‘major’ T20 competitions,” says Rob Barron. He is the head of Cricket for Decimal Data Services, a company that makes odds for betting companies. “Sometimes the market seemingly pays no attention to the cricket that is happening. For example, it is extremely difficult to make a case that 15/0 off the first over isn’t good for the batting team when stats suggest the over is expected to go for something like 6.5. So what are we supposed to think when the market is telling us that the bowlers have had a great start and makes them 20% more likely to win the match?”

One thing Barron is very clear on is that fixing does not always change markets. “When the odds appear too good to be true, some punters believe the result has been predetermined and scramble to back the team who they think is ‘meant’ to win, thereby skewing the market more, even though there may be nothing at all ‘dodgy’ going on with the cricket itself.”

Many professional punters and syndicates won’t bet on the BPL at all, because they believe the market is so volatile and lopsided. Essentially, it doesn’t follow normal cricket patterns. One other thing insiders told me regularly, is that this is the only league that shares this pattern. There are abnormalities in T20 betting markets around the world, but the BPL has so many that professionals don’t feel comfortable betting on it. The other leagues that share this pattern are usually the T10 competitions.

While I was writing this piece, I was streaming another match, Dhaka Capital vs Sylhet Strikers playing on January 10. As I was talking to a source, they told me that the market believed the score at the end of the sixth over bracket would be more than 65.5 runs. That was very high.

To explain this fully, I need to give you more information on betting brackets. In T20 matches, you can bet on what the scores could be at the end of 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15 and 18 overs. On the bigger ones, like overs 6, 10 and 15, millions can be spent on one money line. People will buy or sell that line, meaning you can bet on the score being higher or lower than that. It will usually change every single ball.

Let’s say the run line for the third over bracket was 22.5 at the start of play, and the opening ball of the first over is hit for six. It will move to 24.5, or even higher still. This is the crucial part, that the line changes. Almost every ball. A dot brings it lower, a four pushes makes it higher. Over the course of three overs, it can vary wildly from ball to ball.

Every bet on the money line is evens - a 50% chance of it happening. If you say they were going to score higher than 22.5, and the batters score 23, you get two dollars back for every one you bet (your original stake back and the same amount as your profit). If the team ends up at 22, you get nothing.

At the start of the brackets, people in huge betting syndicates use quantitive mathematics, match-ups, pitch conditions, and weather to make decisions for their six-figure bets. The brackets usually follow a fairly simple pattern: at the start, they are a bit of a guess, and then they become more of a science as people can work out what bowlers will be used, see what the wicket is doing, and gauge the batters’ intent.

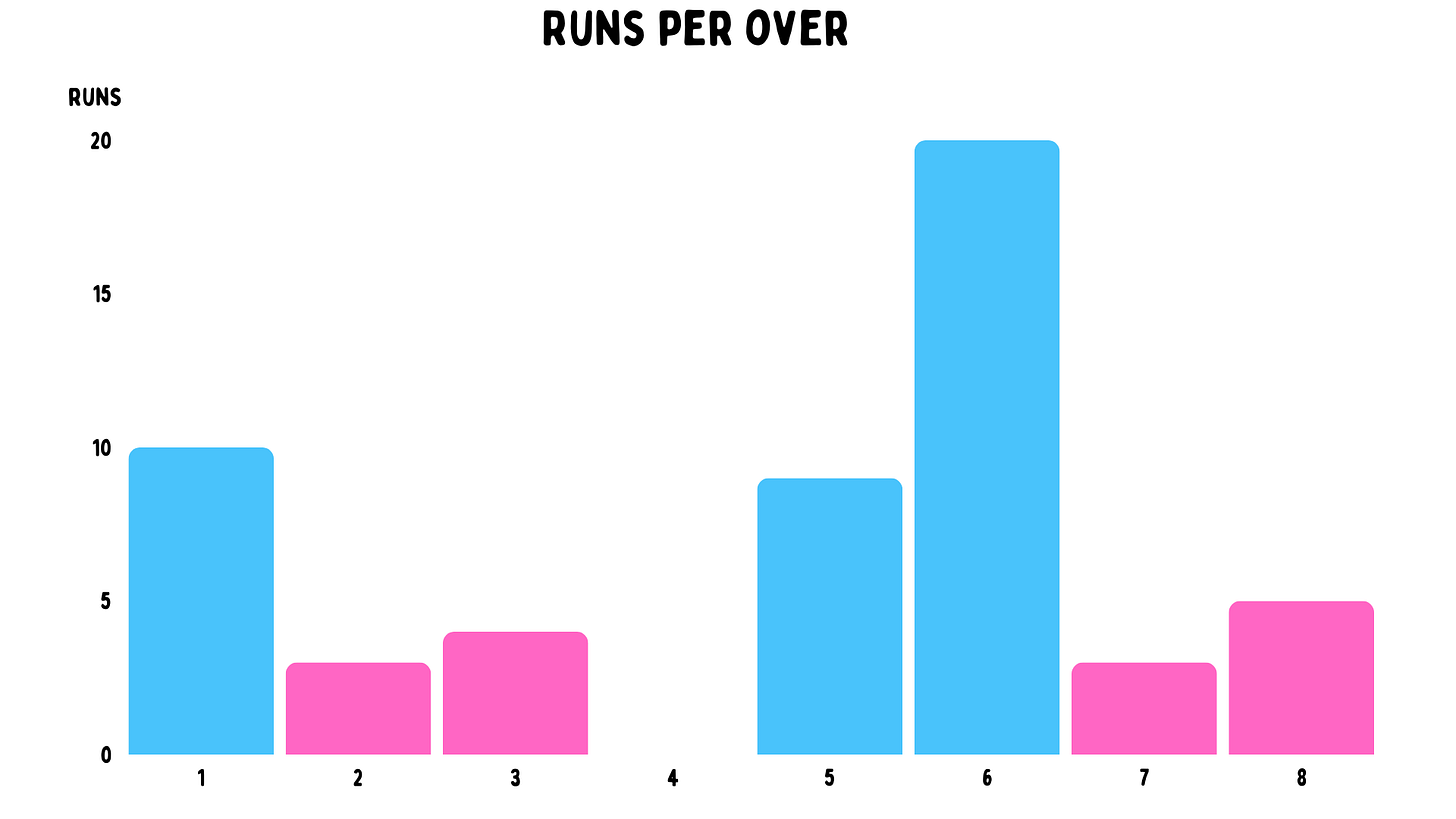

So that game on January 10, the six over run line suggested the score would be over 66 runs. At that stage, the score was 19/2, with the team’s two main overseas hitters out. They were scoring at 9.5 runs per over, but needed to score almost two runs a ball from then on in to make it to 66. It was unlikely. And with a new batter at the crease, even less so. And from a cricketing point of view, not a usual 50% chance as the odds suggested.

The third over had nine runs scored, so it was slightly behind what was needed, but even with fewer runs scored than the rate required to make it to 66, the run line did not come down. The following over made more sense with two sixes smashed in a row, and 14 runs from the over. For the first time, 66 runs seemed very possible.

However, 24 runs were still needed from two overs to reach the total, which is a lot, even for the end of the powerplay. At the death 12 runs an over is not guaranteed.

It became less likely when the first ball of the fifth over was fired past the pads and flicked to short fine leg to be caught. This was an issue, as Aaron Jones, who’d smashed the two sixes, was out and another new bat, with a low career strike rate, was in.

They needed 24 runs in 12 balls, and then in 11 balls, but the run line didn’t come lower. It did actually change after the wicket, it went up a run. At 41/2 in four overs, a score of 66 was a 50% chance, at 4.1 overs with the score 41/3, a score of 67 was a 50% chance. The wicket of someone who had smashed 14 off 8 balls made it more likely to score more than two runs a ball according to the market.

The next ball was a wide, a big one fired down leg, and then fumbled by the keeper — which allowed the better hitter to come to the striker’s end.

Then another wide. Followed by a big six, then a misfield with a very slow chase. This meant that at the end of the fifth over, the batting team needed a minimum of 11 runs to beat the 66 score the market was suggesting.

The bowler for the sixth over was a part-timer in his fourth BPL match. Generally, the last over of the powerplay is usually delivered by a skilled frontliner, not a part-timer. The first ball was a half volley on leg stump that got the in-form batter on strike. The next ball was a wide full toss smashed to cover for a boundary.

Then a dot ball, but again it was misfielded. The next delivery was a wide. Then one aimed at the pads and it was helped away for a boundary. The score was now 65, but the following ball was short and wide, a really horror delivery, and cut for another boundary. With the score already over 66, there was still another wide, this time it missed the pitch, and was a no-ball as well. In total, the over went for 19 runs.

The 66 runs needed for the bracket was a 25% chance according to me at some points with three wickets falling, and ended up being breached with deliveries to spare by one of the worst sixth overs I have ever seen. This all happened with a team three wickets down (which usually means sides slow down, especially when their overseas players are out). They needed 25 runs from 11 balls to reach the run-line with a new slow batter at the crease. Yet, they did it easily.

Here is a collection of the balls delivered in the fifth and sixth overs: a couple of legside half volleys, a wide full toss, a length ball down leg, short wide filth, a ball that did not touch the pitch, and a wide half-volley for the free hit.

That brings us back to our game at the top, the wides on January 7 between Dhaka Capital and Rangpur Riders.

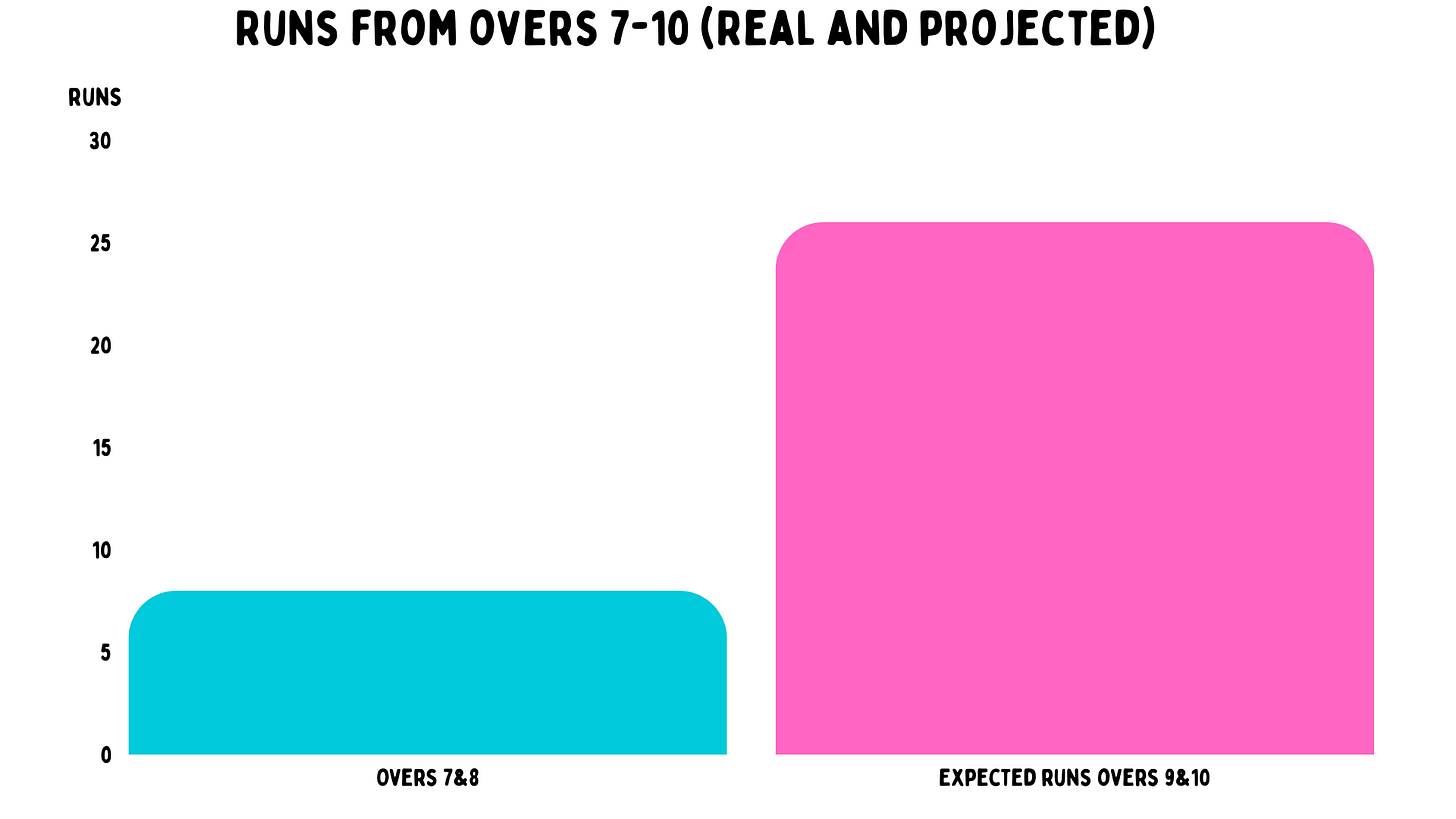

After eight overs of Alex Hales smashing it around, the money came in for over 79.5 for the ten over bracket. That meant it was 26 off 12 balls needed. After Hales was dismissed in the ninth over, big money came in again for over 78.5 with 18 needed from eight balls. And when Ifthikhar Ahmed was on strike on one from three balls in the 10th over — having not scored off his last two deliveries — big money again came in with 12 needed off 4 to jump the 78.5.

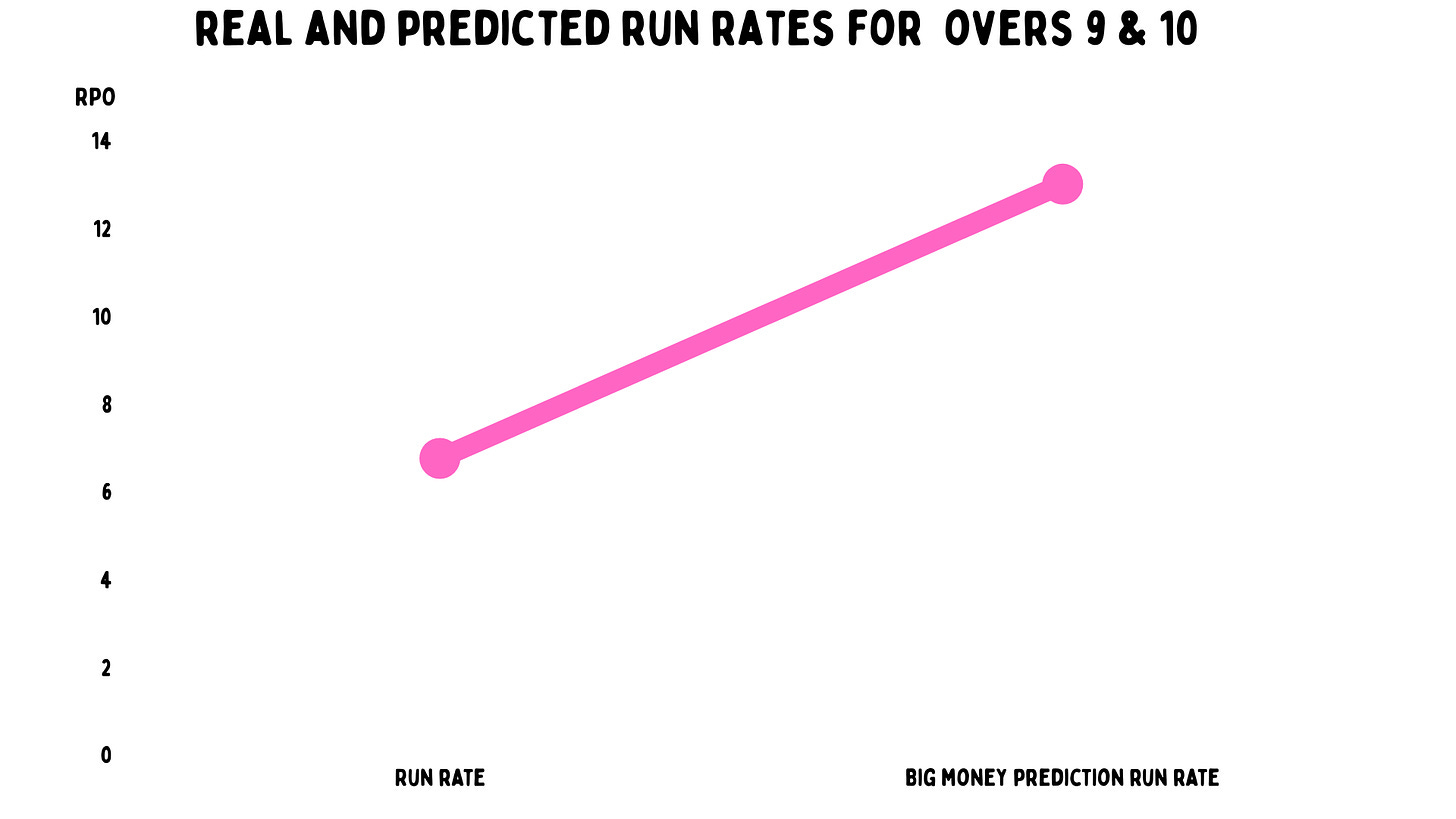

Let’s go back to the end of the eighth over. In the seventh, Curtly Ambrose said on commentary, “They’ve all but given up” about Rangpur Riders. Hales had been smashing the ball, but that was in the powerplay. At this stage the runs needed were very high, 13 runs an over to breach the 78.5. Even with Hales’ powerplay bashing, their run-rate was only 6.75.

So the big money bets were that they would double their current run-rate. That is not very likely, certainly not a 50% chance.

There really hadn’t been many runs scored since the extra three fielders went out of the circle at the end of the sixth over. The seventh over went for three, and the eighth for five.

So now, more than three times as many runs were about to come from the next two overs according to large bets. Hales had blocked a ball in the eighth over, and really, no high-intent boundary shots were tried that over at all.

The only really big over was at the end of the previous bracket, when the total was supersized by 20 runs in the sixth over.

In the ninth over Hales hits a six, but is then dismissed going for another. Yet more big bets come in after his wicket, still predicting an over 78.5 run line.

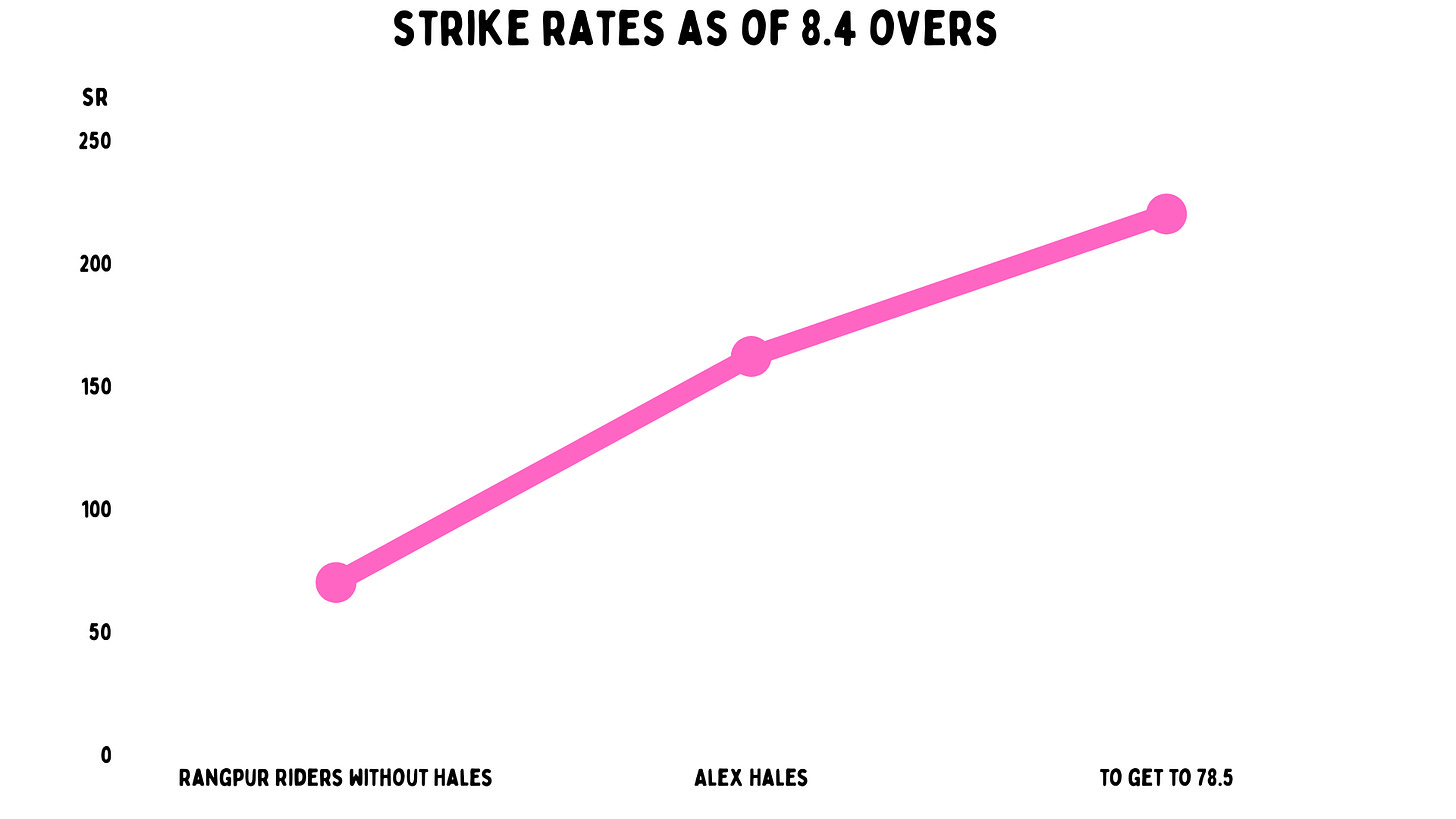

Through to 8.4 overs, they had scored at a strike rate of 119 and people had believed they could up that. Now with Hales out for 44 from 27, they still thought this team would score at a 225 rate.

Of course the team wasn’t scoring at that rate around him. Without Hales, their collective strike rate was 70. They would need to up that strike rate to 220 to score 18 runs from 8 balls, and beat the run line. That isn’t a 50% chance.

The new batter is Iftikhar Ahmed, who is a big hitter, but he pushes his first ball for a single. So that means 17 runs are now needed from 7 balls. The next ball from the offspinner is down the legside.

Not a little bit, it pitches outside legstump, while spinning further away from the stumps, at pace, and then flies down to the boundary for five wides. 17 from 7 becomes 12 from 7, and then 12 from 6 with a dot ball to finish the over.

The bowler who delivered the sixth over for 20 runs is brought back for the tenth. The first ball is a nice yorker, dug out by Iftikhar to midwicket for no run. The next is a length ball outside offstump pushed to point for another dot. So now 12 is needed from 4 balls, and this is when the final big bets come. Three runs a ball after two dots should logically be far from a 50% chance of happening, despite what the market now says.

A slower ball is delivered outside offstump, Iftikhar tries to smash it, but hits it straight up in the air and Jason Roy comes in to drop the catch at long on. He misjudges a huge skier, and they take a single.

Next ball Saif Hassan receives a slower short ball that he pulls away to the boundary to pick up four runs. To follow that, Saif runs down the wicket, gets a short ball and mishits it out to deep point and is caught.

So now the bet lines have changed, because fans at home are watching this and the 78.5 can no longer be breached. Because of that, the Rangpur Riders would need to score seven runs from one ball.

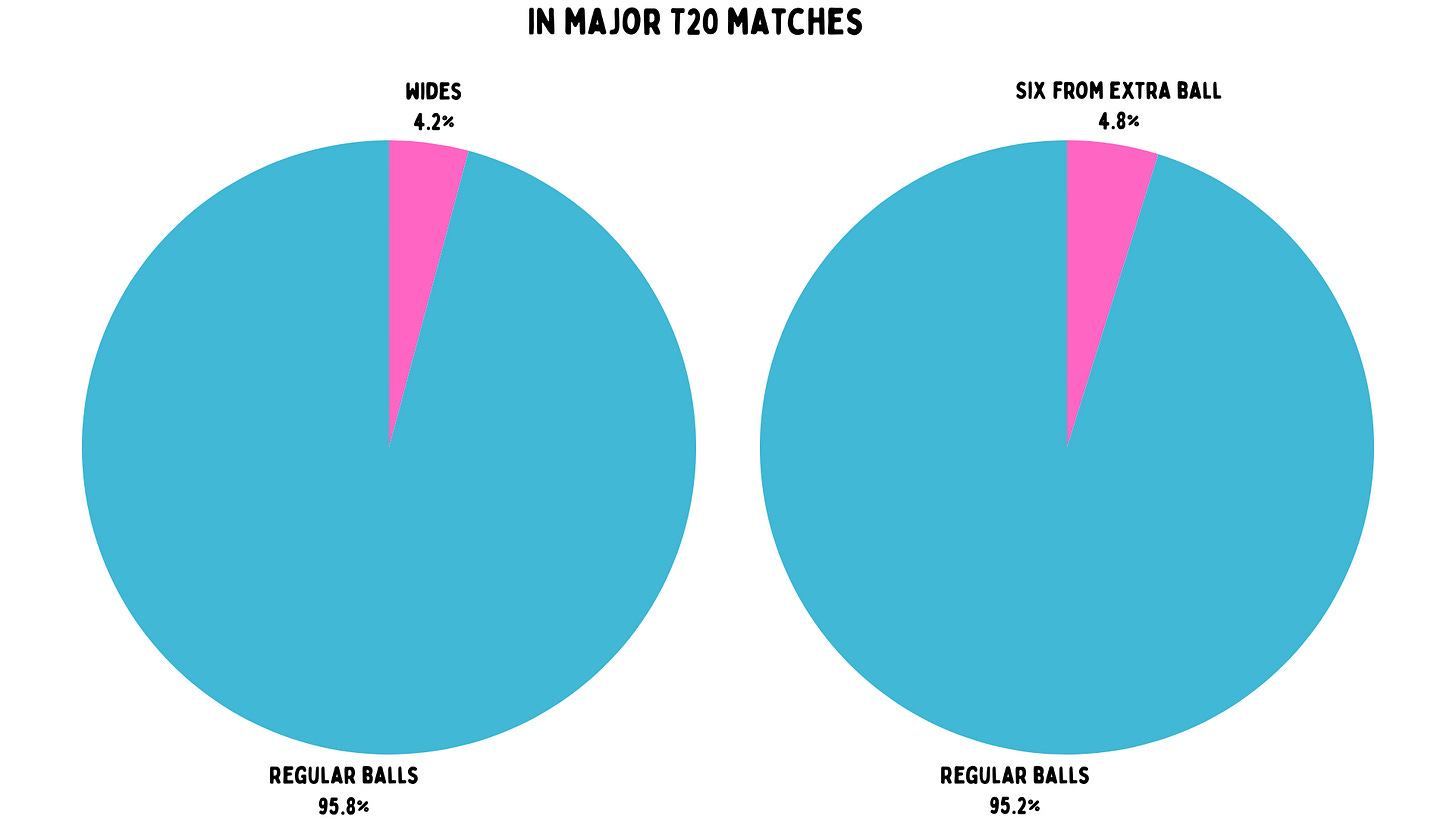

The chances of seven runs off a delivery is pretty low. We did the math: 4.17% of balls in T20 are wides or no balls, and another 4.8% are hit for six when there is an extra ball bowled off the over. So the chances of these two combining (or really any other methods, like a no-ball four followed by a two, four overthrows after a three) are at best, less than 4.8%, but, really, are way less than 2%.

Maybe it is as low as 0.2%. About one in 500. So even if we are friendly and say it’s a one per cent chance, that means the odds on seven runs coming in the last ball should have been something like 100 to one.

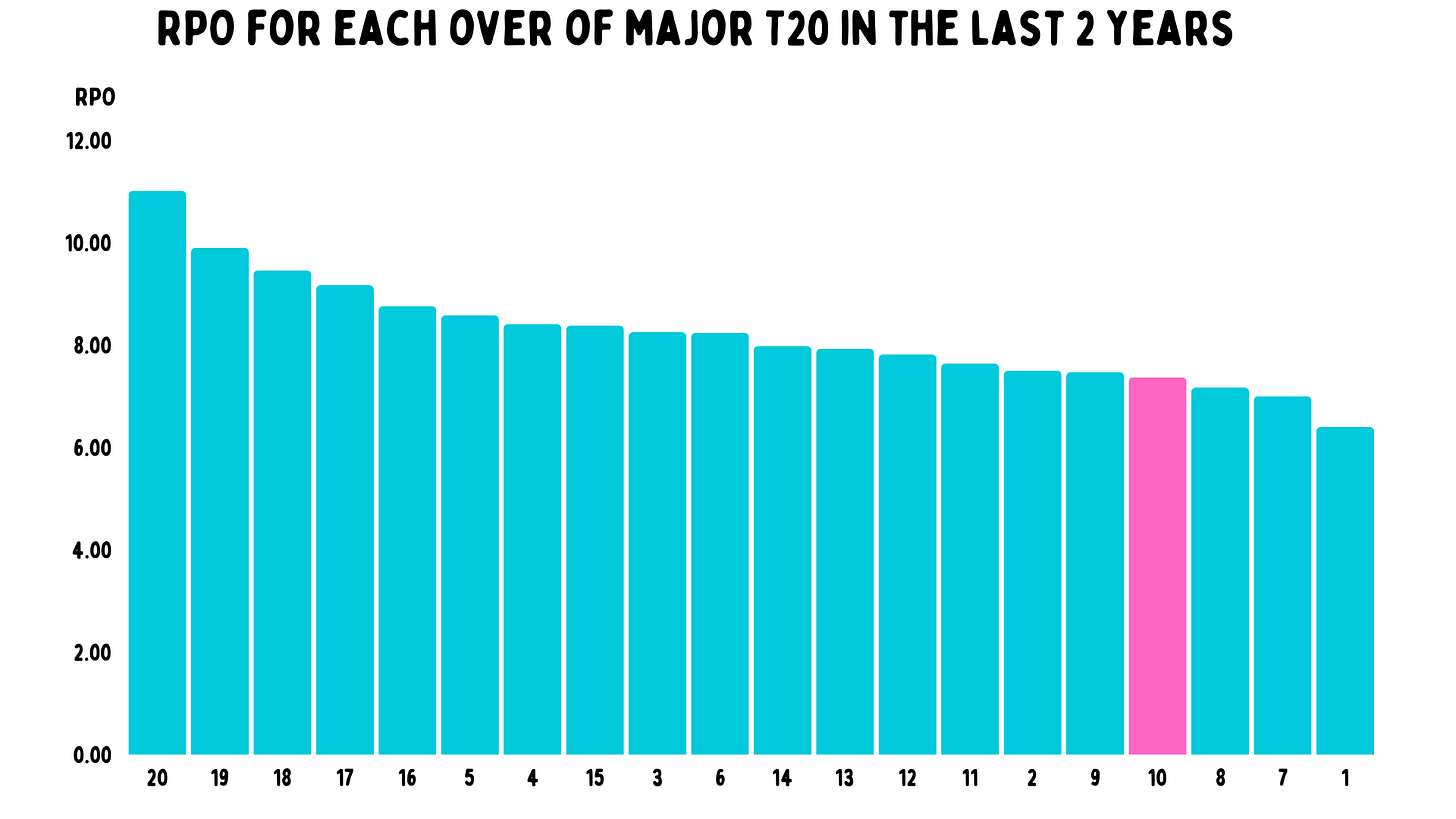

Remember, this was the tenth over of the match, which is not one of the highest-yielding overs.

In this case, because the chasing team was on top, you could argue that they were putting their foot down. But we need to add one more factor here: the batter at the crease was facing their first ball.

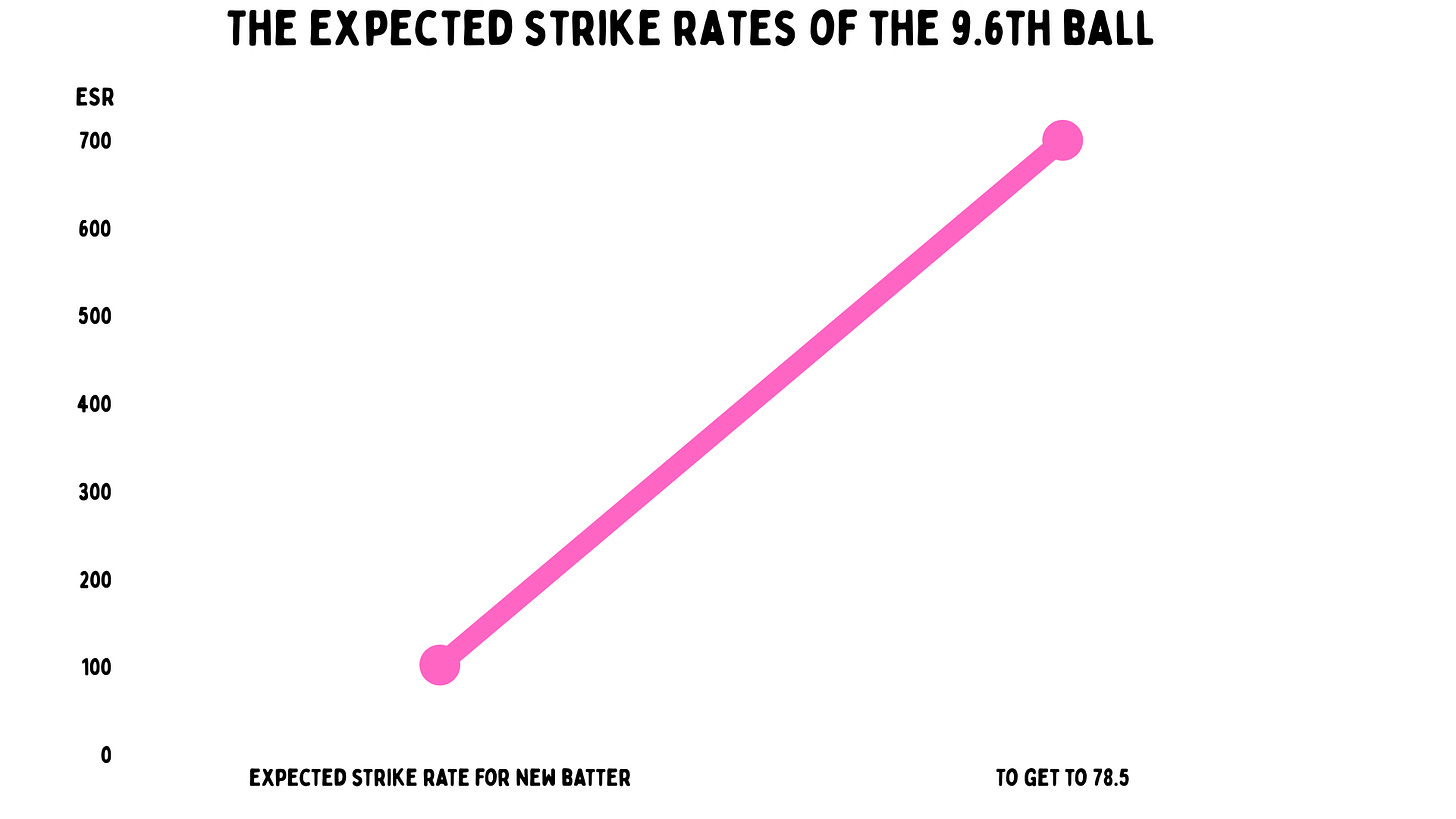

So with the score 72/3, Khushdil Shah comes out to face his first ball (the 9.6th), and to satisfy all those big bets he needs to score a seemingly impossible seven runs off it. We checked his expected strike from this delivery and it was 102.

Later in his innings, he would go on to smash the ball around for 27 from 13, and so clearly, he was going to score faster than he usually did. But no batter in the world can score seven runs in one ball without overthrows or the bowler conceding extras.

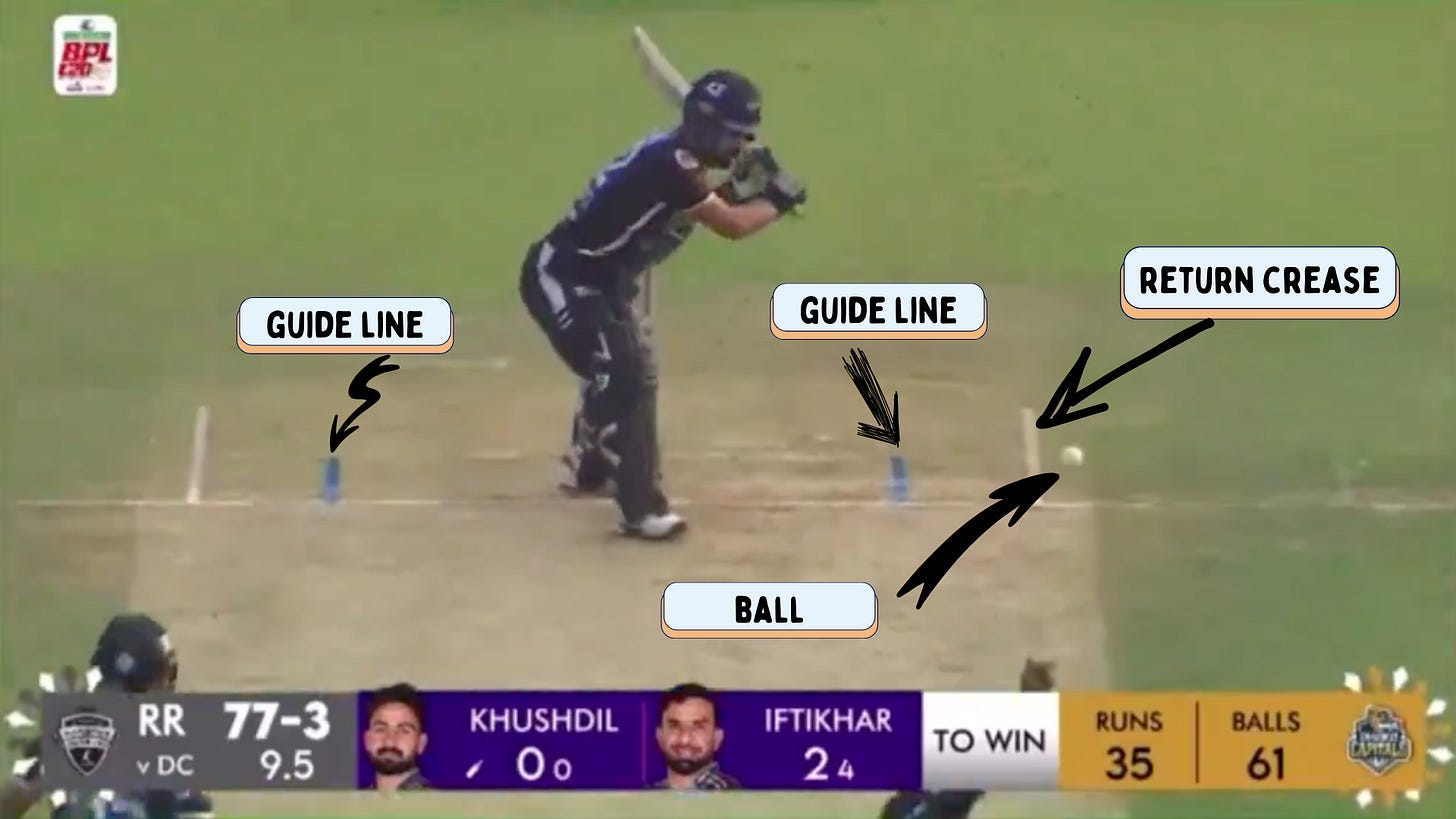

For his first delivery, the left-handed Khushdil did not have to do anything at all. The seam bowler, coming from right-arm around the wicket, pitched the delivery short and outside leg stump. The ball passed the batter not just down legside (which is obviously a wide), but outside the return crease.

This is a big wide. The commentator Shamim Chowdhury says, “Oh my goodness, that’s possibly a no-ball, where did it land, on the other pitch? What’s going on here?” Curtly Ambrose follows up by saying “What kind of delivery was that?”

The follow-up ball was also a huge wide. Not just outside the guideline but almost completely off the pitch. So two deliveries in this T20 match right after taking a wicket have been outside the crease lines.

This was followed by one more wide. Again, it’s not touch and go, it is around 50 centimetres outside legstump as the bowler has changed sides from around to over.

(Video of the wides can be found here, thanks to Ravi Layer; it was his tweets that were passed to me by people in the betting industry.)

These are the last three balls that were bowled, if you need them all in front of you.

They aren’t close calls, the umpires weren’t too quick on the trigger. It isn’t bouncers to a new batter that went wrong, or wide yorkers just outside the blue line. These are huge wides, in a row.

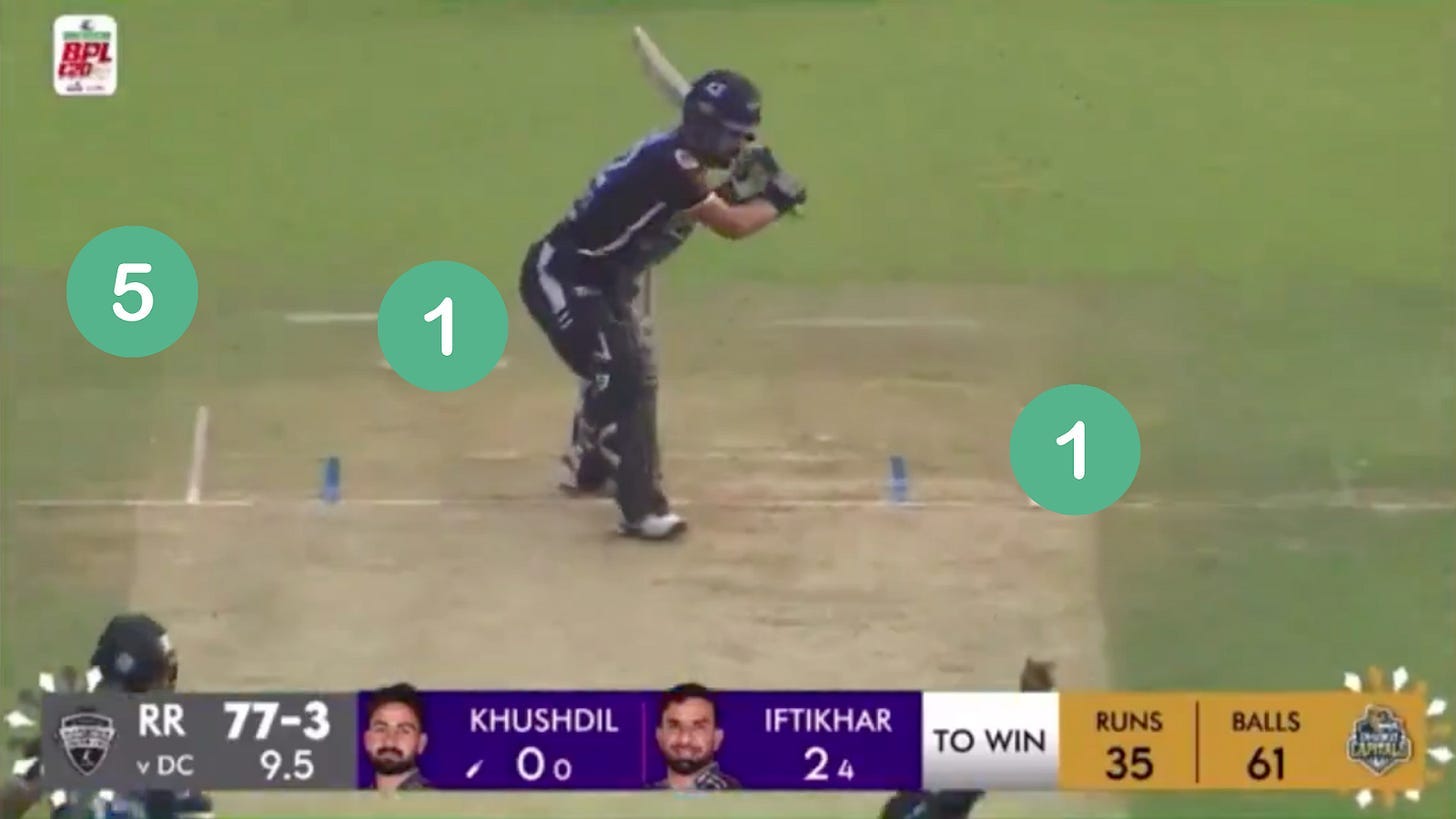

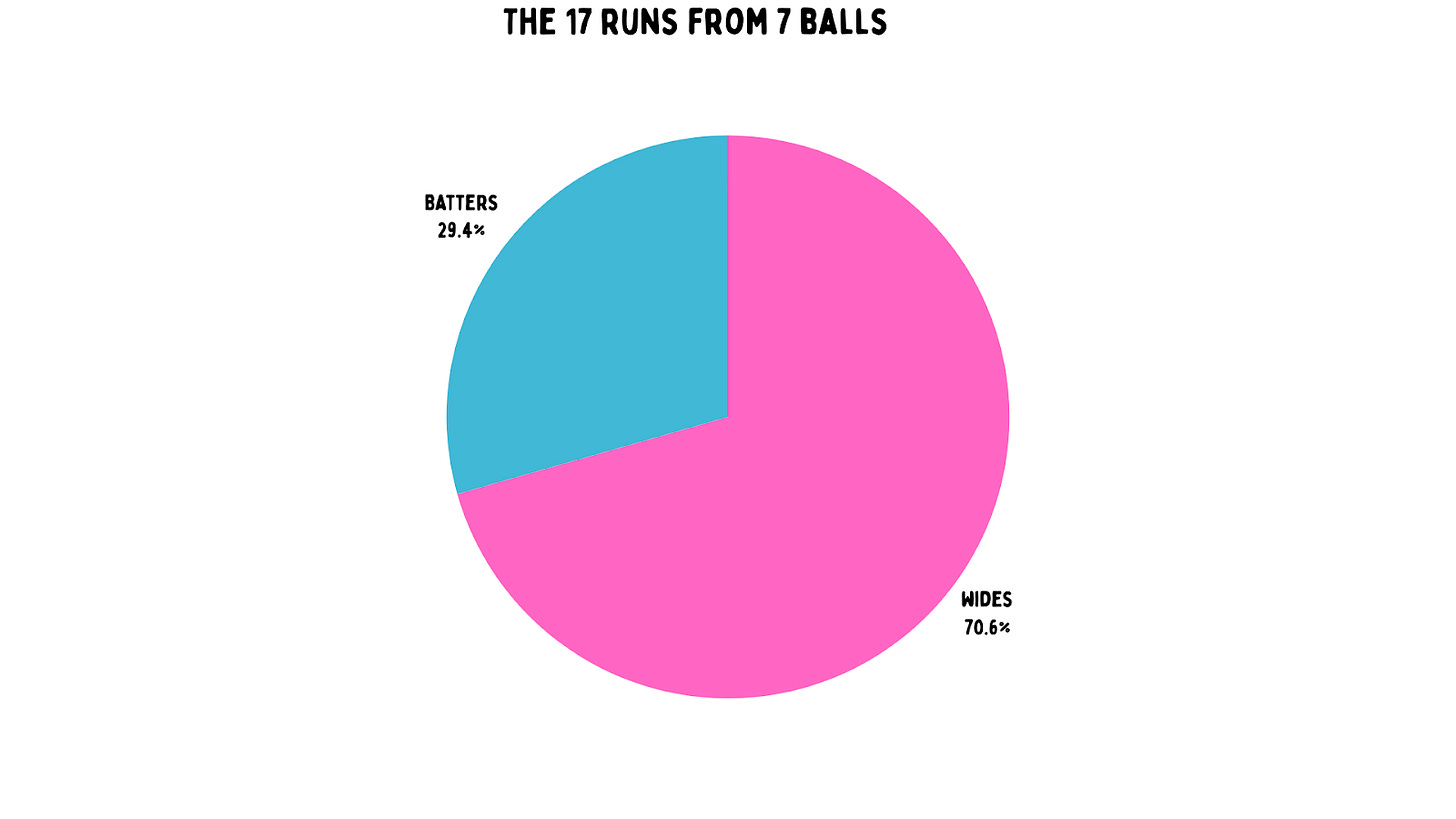

This is how many runs each of these balls went for. The first one that went flying down the legside also went to the boundary, so one run for the wide, four more wides for the boundary. The other two are normal wides. Do you need me to add this together for you, or are you there already? The total is seven runs.

That means the big market bets were right, this bracket did go above 78.5 runs.

At the start, we said we checked how often three wides have gone back-to-back-to-back in our database for the tenth over. We had 2919 overs, and this was the third time it ever happened. So 0.1% of the time.

But at one stage the run line needed 17 runs from 7 balls to hit its over, and 12 of those runs came from wides.

We checked how often 12 or more wides had been scored from a 17-run period in the first ten overs of T20 games. We found four before this in 8245 matches. We tried to put this on a graphic, but it looked stupid, so you may just have to use your head.

You will notice we have named some players in this piece. Everything we saw them doing is perfectly normal. Some of these players like Munsey and Cornwall, I have worked with before when I was an analyst and general manager. I am not accusing any player of fixing here, even those not mentioned. I am merely telling you the story of something that actually happened.

This is what we do know: three huge bets came into a 50/50 betting market despite the match conditions suggesting they were far less likely than that. The only person scoring runs was dismissed, yet more money came in. More cash was laid again with a new batter on strike and three runs needed per ball. According to our stats, three wides in a row for the tenth over happens every 1000 matches. And 12 or more wides in 17 runs in the first half of T20 matches happens every 2000 matches.

People bet very big money on the run line being over 78.5, and they kept betting on it even as it became less likely. And then, when it looked like it was impossible, we saw a 1000-1 and 2000-1 occurrence happen.

Shamim Chowdhury said after the third wide, “This is unbelievable. This is unacceptable.”

We contacted the ICC, Betfair and the BCB on this story. Betfair said they would try and find someone for us, but did not provide an answer in time. The ICC told us they are not in charge of this tournament as the BCB is running it. We emailed the BCB, and the email bounced back.